Sorry, I’m diverting off course slightly here, but one of the things I love about history is being able to see things which have remained relatively unchanged from what our ancestors would have seen. Walking up old stair cases which have a groove worn out due to centuries of use! It really brings the past alive for me. I was just going through some of my photos and came across this beautiful (and over used!) view of Durham Cathedral. Seems the Victorians loved it too! Considering the cathedral has been there (in its current state) since the 13th century I wonder how many people have stood on that spot!

Vol 2 – No. 22, December 1888 – The Great Fire in Newcastle and Gateshead

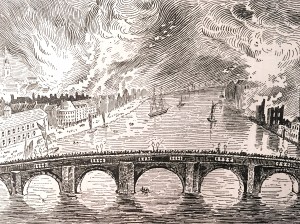

At an early hour on the morning of the 6th October, 1854, there occurred one of the most appalling catastrophes that ever visited the towns of Newcastle and Gateshead. A little after midnight on that day (Thursday), fire broke out in the premises of a worsted factory, on the Gateshead side of the river, belonging to Messrs. J. Wilson and Sons. Like most buildings in which extensive machinery is planted upon wooden floors, this factory might be said to have been steeped in oil; and it was therefore entirely gutted from roof to cellar in less than an hour. A large stone-built building, known as Bertram’s Warehouse, adjoined the worsted factory on the east and the flames very soon spread to it. This building, “double fire-proof,” and seven storeys high, had been originally built for storing goods by Messrs. Bertram and Spencer, but had for some time been used by the merchants of Newcastle and Gateshead as a free warehouse for all sorts of merchandise; and at the time of the fire it was stated to contain 200 tons of iron, 800 tons of lead, 170 tons of manganese, 130 tons of nitrate of soda, 3,000 tons of brimstone, 4,000 tons of guano, 10 tons of alum, 5 tons of arsenic, 30 tons of copperas, 1½ tons of naphtha, and 240 tons of salt. It being well-known that a quantity of combustible matter was collected in Bertram’s Warehouse, the excitement always provoked by a fire of any kind mounted to intense anxiety. A detachment of the military, fifty strong, hastened over from Newcastle with their barrack engine to the aid of the firemen. Streams of vivid blue flame, proceeding from the sulphur, soon began to pour from the windows of the various flats, affording a most extraordinary spectacle; and by three o’clock the whole range was one immense sheet of fire. The alarm had by this time spread in every direction, and had attracted to the scene a large number of the inhabitants on both sides of the river. The Quayside, Newcastle, affording a full view of the burning property, which immediately fronted the Tyne, was crowded with spectators, not one of whom felt the slightest apprehension that he could stand in any danger there.

About ten minutes past three, a slight report, like that of a rifle, was heard, but it occasioned no movement in the crowd. Some three minutes afterwards, however, the unheeded warning received a terrible fulfilment. The air was rent as by the voice of many thunders, and filled as with the spume of a volcano. The rocky basis of Tyneside trembled, and the vessels lying in the river, chiefly keels, were nearly blown oat of the water by the concussion. Old Tyne Bridge shook as if its firmly compacted stones would part from each other, and the iron-bound High Level quivered on its lofty piers as if in a mighty struggle for a prolonged existence. No description can give the slightest idea of the destruction that had taken place, literally in the clap of a hand. Burning piles of brimstone, with bricks, stones, metal, and articles of every description, were thrown up with the force of a volcanic eruption, only to fall with corresponding momentum upon the dense masses of the people assembled, and upon all the surrounding houses. The crowd upon the Quayside and Sandhill was mowed down as by a charge of artillery, many being rendered insensible from the shock, others temporarily suffocated by the vapour, and many more wounded by the flying debris.

An awful calm succeeded for a few seconds, and then, as most of the sufferers regained consciousness, an appalling wail of distress arose in all directions; but many were far removed from all earthly suffering, and their voices were never heard again. The fearful extent of the calamity was now perceptible. The ignited missiles had penetrated into three houses upon the Quayside, standing exactly opposite the fire, to such a prodigious extent that they were in flames in every storey in less than five minutes. The shop fronts and windows on the Quayside, the Sandhill, the Side, and all the neighbouring streets, were almost universally demolished; and the gaslights, for a square mile around the spot, were extinguished in a moment, adding a weird and horrible confusion to the scene. The vibration was distinctly felt at Shields and Sunderland. The workmen at Monkwearmouth Colliery, then the deepest in the kingdom, and at least eleven miles away, heard the explosion, and, it is said, came to bank in alarm. Westward as far as Hexham, twenty miles away; in the north, at Alnwick, thirty-five miles; and south as far as Hartlepool, near forty miles distant, the report was likewise heard, as well as for, at least, twenty miles out at sea. And the flames were distinctly seen during the conflagration at Smeaton, near Northallerton, as well as from Beacon Hill, in the same neighbourhood, about fifty miles to the south.

Of the fifty soldiers of the 26th Regiment who were advancing with their engine to play on the burning warehouse and factory, thirty were struck down – two of them dead, and one with an iron rail driven into his body. Firemen and helping citizens were crushed where they stood, in the narrow roadway of Hillgate, Grateshead, within a dozen yards of the doomed buildings, when the rubbish fell upon them in tons together, causing instantaneous death. Others, looking on in helpless excitement, were in a moment stricken beyond consciousness by the suffocating fumes, which continued, we may mention, to be so pungent during the whole of the next day as to render it painful to inhale them anywhere near, or even to draw a full breath when passing over Tyne Bridge. Amongst those who were buried several feet deep among the ruins in Hillgate, were Mr. Robt. Pattinson, tanner, a member of the Newcastle Council, whose hobby was the fire-engine, and who made it a point of duty to help the firemen everywhere pending their better organization; Mr. Charles Bertram, a magistrate of Gateshead; Mr. Henry Harrison, basket maker; Mr. William Davidson, son of Mr. Davidson, miller (whose extensive premises were within a few feet of the fire, and were afterwards consumed); Mr. Alexander Dobson, son of Mr. John Dobson, architect; Mr. Thomas Sharp a gentleman of independent means; and Ensign Paynter, of the 26th Regiment.

Of course the explosion greatly increased the extent of the fire in Gateshead. Besides Davidson’s flour mill, Wilson’s worsted manufactory, and Bertram’s warehouse, already mentioned, the following premises of different kinds were totally destroyed :-Mr. Bulcraig’s engineering works, Messrs. J. T. Carr and Co’s timber yard, Mr. Singers’s vinegar manufactory, Mr. Martin Dunn’s timber yard, Mr. Wilson’s fellmongery, and a number of tenemented houses and small shops in Hillgate. Church Walk was almost entirely demolished, with many houses in Bridge Street, the Bottle Bank, Oakwellgate, &c., which it is impossible to enumerate; and St. Mary’s Church was saved from destruction only by the courage and energy of Mr. James Mather, of South Shields, who got into the sacred building at the risk of his life, and by means of an engine-pipe which was handed to him, and an axe for which he called, rescued it from the power of the insatiable element.

On the Newcastle side of the river the destruction was more awful and alarming still. It has already been said that the fire broke out in three houses on the Quayside, opposite the warehouse in Gateshead, where the explosion took place. The shops of these premises were occupied by Messrs. Smith and Ca, drapers; Messrs. Ormston and Smith, stationers; and Mr. Harbottle, draper. Besides these premises, the shop of Messrs. Spencer and Son, drapers, and the offices above (one of which was occupied by Mr. Bertram, whose death we have recorded, were almost entirely reduced to ruins by stones projected from the site of the explosion. The property immediately behind Messrs. Ormston and Smith’s was the Dun Cow, in the occupation of Mr. Teasdale, and the spirits which it contained immediately gave increased energies to the flames, which consumed the whole fabric in less than half-an-hour. The fire then gradually progressed both north and east, making its way in the first direction up Grinding Chare, principally through old warehouses, toward the Butcher Bank, and, in the second, along the range of buildings on the Quayside. The shops of Mr. Atkin, bookseller, and Mr. Tumboll, watchmaker, as well as the Grey Horse Inn, succeeded Messrs. Smith and Co’s; and the flames ran thence to the northward, up Blue Anchor Chare and Pallister Chare towards the Butcher Bank. By six o’clock the fire had spread along the Quayside for nearly one hundred and twenty yards, while the extent of it towards the Butcher Bank was rather greater, the fire having traveled up the whole length of Blue Anchor Chare, Peppercorn Chare, Pallister Chare, and Homsby’s Chare, and made a breach into the Butcher Bank by three separate houses, all of which were entirely consumed. A blazing beam of timber, thrown by the explosion high over the Butcher Bank, fell into the workshops of Mr. J. Edgar, situate behind his premises in Pilgrim Street Here the flames worked their way uncontrolled, destroying a front shop occupied by Mrs. Ann Shield, grocer, on one side, and a large number of tenemented dwellings and workshops adjoining George’s Stairs on the other.

When the sun rose, never had his rays exhibited Newcastle in so awful a state as on that October morning. The fire was still extending widely amongst the property near the Quayside, whilst the flames in Gateshead were quite unsubdued, there being, indeed, no means of checking them there, owing to the fire-engines having been almost entirely buried in the ruins.

Soon as the tremendous shock ceased, however, were seen the workings of those faculties in the use of which man looks godlike. No moment of precious time was lost in timid flight or useless wailing. Sorrow was put off in the agony of present strife. The engine of the North Eastern Railway Company was fortunately uninjured, and proved of great service on the Quayside. Communications were sent by telegraph to all the neighbouring towns for assistance. The floating engines at Shields and Sunderland, three land engines from the latter town, and one each from Hexham, Durham, Morpeth, and Berwick were despatched by the authorities of these places. Fresh soldiers replaced their disabled comrades. The vessels that were in danger were moved out of the way, and in those that had been touched by the lighted brands the fire was extinguished. Happily, there was no wind. Thus encouraged, as many as could get near enough to help worked as one man. No danger — not the hot embers nor the shaking walls — deterred the firemen from carrying their hose, or the excavators from moving on with their picks; while every leaping jet of water and courageous venture on to some coign of ‘vantage was cheered by the impatient lookers-on.

As the uninjured regained their presence of mind, every endeavour was made to render relief to the wounded, numbers of whom were carried off on boards and shutters to the Gateshead Dispensary; while upwards of a hundred, from both sides of the river, were taken to the Newcastle Infirmary. Never were the resources of that great charity so severely tried. Fifty-eight persons, seriously injured, were at once admitted into the house, fifteen of whom died; while sixty-three others were relieved as out-patients.

On the 7th, the fire was got under on both sides of the river, and immediate steps were taken to disinter the remains of those who were known to be killed in Gateshead. The bodies of Mr. Pattinson, Mr. Hamilton (hairdresser), Ensign Paynter, Corporal Stephenson, Mr. Willis (skinner), Mr. Duke (bricklayer) and his son, a child named Conway, and a labourer named McKenny, were thus recovered. On the 8th the body of Mr. Mosely, a smith, was found much disfigured, and about noon there was discovered a charred and crumbling mass, without the least resemblance to humanity. A piece of the coat and a bunch of keys, lying close by, led to its identification as Mr. Alexander Dobson. The next fragments found were those of Mr. Thomas Sharp, shockingly mangled, and only identified by his gold watch and two dog whistles. Several other bodies were discovered in a similar condition. Mr. Davidson was identified by a signet ring, Mr. Harrison by a cigar case, one of the firemen by the nozzle of the engine pipe, and many others by similar articles known to have belonged to them. In Church Walk were found the family of a man named Hart, consisting of himself, his wife, his son, and his niece. No portion of Mr. Bertram’s body could be found, but a key, which was known to belong to him, and his snuff box, were discovered among the ruins.

A great amount of evidence was tendered at the inquests as to the cause of the explosion, the general opinion being, that nothing but a vast store of gunpowder could have been the cause of the catastrophe. Mr. Hugh Lee Pattinson, the celebrated chemist, offered an explanation of the disaster, which he attributed to the action of water on the chemicals, whilst Dr. Taylor, Professor of Chemistry at King’s College, London, ascribed its origin to gas. Mr. Pattinson believed that the heat of the building had inflamed the sulphur, and that gradually the whole mass of nitrate of soda and sulphur in the lower vaults had melted together, producing intense combustion, and a heat such as could not well be conceived. His assumption was, that a body of water, while the contents of the warehouse were in this state, had found its way to the burning mass, and, by the immense expansive power of steam at such a heat, had caused the explosion. In his opinion, 328 gallons of water, acting in this way, would have as powerful an effect as eight tons of gunpowder. Professor Taylor supposed that the sulphur, having taken fire, had inflamed the nitrate of soda which, he said, would set free half a million cubic feet of gas; and the inability of the gas to escape fast enough through the door of the vault had, be believed, caused the explosion. Both chemists, from various analyses of the ruins, were equally confident that no gunpowder had been present. The juries, after very lengthened sittings, finally came to open verdicts, expressing, however, their belief that the explosion had not arisen from gunpowder.

The loss by this terrible fire was never accurately ascertained, but it was pretty generally estimated at not much short of a million pounds sterling. Whether the loss of life was accurately ascertained at the time is yet a matter of opinion, but the total number known to have perished was no less than fifty-three.

Perhaps no circumstance can better convey the idea of the immense power of the explosion than the fact that it burrowed into the solid earth and undermined the huge granite blocks which formed the tramway for carts in Hillgate, casting these solid stones to an immense perpendicular altitude, so as to soar above St. Mary’s Church, and to project them over it two or three hundred yards into the neighbouring streets. One stone fell through the roof of the Grey Horse, in the High Street of Gateshead, a distance of four hundred yards. Another, nearly four feet long, a foot broad, and eight inches deep, weighing nearly four hundredweight, fell in Oakwellgate, and forced its way into the ground a considerable depth. A third stone, upwards of twenty stone weight, fell through a house in the same street and smashed everything before it. A stone weighing about two hundredweight was blown through one of the high windows of St. Mary’s Church, while another, almost equally ponderous, penetrated the roof, and both were found lying in the pews. Large blocks of wood and stone were also projected considerable distances across the river. One stone was embedded in a house left standing at the west end of the Quay. Another was dashed with such violence as actually to penetrate like a bullet through the wall of the engine house of the Courant office in Pilgrim Street. A stone weighing 18½ pounds fell through the roof of the premises of Mr. Hewitson, optician, in Grey Street; and this stone, when the workmen came in the morning, was found too hot to be handled. A huge beam of timber about six feet long was hurled upon the roof of All Saints’ Church; another piece, about ten feet long, eight inches square, and weighing three hundredweight, was thrown upon the Ridley Arms Inn, in Pilgrim Street; another went vertically through the roof of the Blue Posts Inn in the same street; and yet another alighted upon the roof of a house in Mosley Street These latter locations were distant about three-quarters of a mile from the point of projection.

Many strange escapes were recorded at the time of the disaster. Not the least remarkable of these circumstances was the discovery the day after the fire of two children in a house in Hillgate, one in a cradle and the other in a closet both alive and uninjured, but desperately hungry.

The intense interest in the fire caused the streets in the neighbourhood to be thronged like a fair the whole of Friday, the day after the disaster; on the Saturday, the numbers were considerably augmented by the market people from the country; and on the Sunday the numbers were almost beyond estimate. Not less than twenty thousand strangers came by rail that day; special trains ran every hour; and such was the anxiety of the people that many had to wait for hours at the stations before they could get forward. Some came to sympathise with the injured, others to mourn with the bereaved, while the greater number, having breathed the noxious and polluted atmosphere which pervaded the town during the whole of the day, returned in the evening with the deep conviction that they would “never look upon the like again.” The public sympathy for the poor people who were rendered destitute by this terrible catastrophe was displayed in the most marked manner throughout the kingdom. Upwards of £11,000 were subscribed for their relief. No fewer than eight hundred families applied for assistance from the fund, and altogether £4,640 was paid for the loss of furniture. In February, 1857, the committee which had charge of the subscriptions stated that £6,533 had been expended, that £3,844 had been reserved for widows and orphans, and that the remainder of the fund was distributed as follows : Newcastle Infirmary, £1,190; Gateshead Dispensary, £314; Bagged Schools, £195; other charities, &c., £50.

Our sketch of the fire, showing the view from the High Level Bridge, with Tyne Bridge in the foreground, is taken from a drawing by Thomas Hardy, kindly lent us by Mr. Thomas Bell, Pilgrim Street, Newcastle.

Vol 2 – No. 16 – June 1888 – An Old Soldier

CHARLES McINTOSH, who has long been a familiar figure in Sunderland, was born on 22nd of March, 1793, at Meerut, in India, where the 71st Highland Light Infantry was at that time quartered. He was “a child of the regiment”, for his father was a private in the ranks, having been drafted from the Inverness Militia into the 71st at its embodiment on Glasgow Green. This waif and stray of the barrack yard was often packed away with his mother on the baggage waggon. So soon as he was able he became a drummer-boy in the regiment. He was with his father’s regiment in India up to the settlement of the Mahratta difficulty. At the age of 13 years, he landed with the 71st at the Cape of Good Hope, which was captured by the expedition under Baird and Popham. No sooner had the 71st arrived home than it was placed under orders to join the expedition which Wellington led to the Peninsula in 1806. This now famous regiment, incorporated with the historical Light Brigade, took part in the first brush with the enemy after landing at Mondego— called the battle of Roleia. During the terrific conflict at Vimiera the regiment was closely engaged in a hand-to-hand fight. Wellington was afterwards superseded, much to the regret of the soldiers. The Light Brigade was then incorporated with Sir John Moore’s force. A memorable episode of its career was that disastrous of the British army over the snow-covered mountains of Galicia to Corunna. The remnants of the army were severely handled in the hot and sanguinary battle which was fought close to the walls of the sea port. In this engagement, the drummer-boy (McIntosh) was wounded on the inside of his left thigh by a spent ball. Through loss of blood, he fell among the dead and wounded which thickly strewed the ground. After recovering his senses, he found himself face to face with a wounded French officer, who levelled a horse pistol at him; but the agile drummer-boy quietly drew his dirk from his stocking, and thus saved his life. Wellington again resumed command, and then followed that glorious list of engagements that ended at Toulouse. Happily the “little peace”, as it was termed, gave Europe a welcome rest from the toils of warfare. Charles McIntosh, with his father, had served with the 7lst Regiment throughout the five years of incessant campaigning which preceded it. On the re-organization of the regiment, his father left the service, and claimed also his son’s discharge, he being then 21 years of age. The family settled in Glasgow, where Charlie learned the trade of a hatter, working as a journeyman both in that city and at Perth. The military instinct was, however, not extinguished, so in 1828 be took “the king’s shilling,” and enlisted in the 79th Highlanders. With this corps he embarked for British North America. Whilst serving in Canada in 1851, he was struck by lightning, and suffered severely from the shock. After quitting the regimental hospital, he was sent home to the depot, and as the result of an examination he was discharged with a pension of 6d. per day to continue for eighteen months, on the understanding that he would submit himself to the medical officer of the garrison at the expiration of that period. At the second examination he was found unfit for further service, and his pension of 6d. per day was continued. McIntosh became once more a civilian, and followed his former trade as a journeyman hatter with Mr. Samuel Turner, Hyde Lane, Cheshire. In 1848, the Chartist movement was in full swing, and McIntosh joined it. Many Chartists, accused of seditious practices, were brought before the magistrates, McIntosh among the rest. Finding on the Bench his former master, he appealed to him for a good word, requesting also that the magistrates should write to the officers of the 79th Regiment touching his character and pension. An excellent record was returned from the 79th Regiment, and McIntosh was discharged from custody. But from that day to this, he says, he has never received his pension. Major Sladden, of Sunderland, has kindly endeavoured to get the pension restored, but the loss of McIntosh’s regimental pocket ledger, containing his discharge, which he left at the Military Hospital, Forepit, near Stroud, has, with other discrepancies, prevented him from succeeding. Familiar to every inhabitant of Sunderland is the fine military figure of “Old Charley,” who for many years past has perambulated the streets with his little satchel of fancy wares. Calling at the principal public and private offices and banks of the town, he has become a general favourite through his pleasant manners and clean and tidy appearance. Up to last October, he was out daily, winter and summer, wet or dry. Having missed him from the streets, I felt there must be some urgent reason for his absence. I found he was ill, and confined to bed, without any means of livelihood. An appeal was, therefore, made to the public, through the kindness of the Editor of the Newcastle Weekly Chronicle the result being the establishment of a fund from which he has received sums varying from ten to twenty shillings per week, which fund has been largely supplemented from other sources. It is sincerely hoped that the “old soldier” will still be kindly remembered, until he answers the last call.

Vol 4 – No. 39 – May 1887 – Cutty Soams

Probably the most dismal place in the universal world is the “goaf,” the sooty, cavernous void left in a coal mine after the removal of the coal. The actual terrors of this gloomy cavity, with its sinking, cracked roof and upheaving or ” creeping ” floor, huge fragments of shale or “following stone” overhead, quivering ready to fall, and “blind passages that lead to nothing “and nowhere, save death to the hapless being who chances to stray into them in the dark and loses his way, as in the Catacombs. These terrors formerly had superadded to them others of a yet more appalling nature, in the shape of grim goblins that haunted the wastes deserted by busy men, and either lured the unwary wanderer into them to certain destruction, or issued from them to play mischievous pranks in the workings, tampering with the brattices so as to divert or stop the air-currents, hiding the men’s gear, blunting the hewers’ picks, frightening the putters with dismal groans and growls, exhibiting deceptive blue lights, and every now and then choking scores of men and boys with deadly gases.

One of the spectres of the mine now, like all his brethren, only a traditionary as well as a shadowy being used to be known by the name of Cutty Soams. Belonging, of course, to the genus boggle, he partook of the special nature of the brownie. His disposition was purely mischievous, yet he condescended sometimes to do good in an indirect way. Thus he would occasionally pounce upon and thrash soundly some unpopular overman or deputy-viewer, and would often gratify his petty malignity at the expense of shabby owners, causing them vexatious outlay for which there would otherwise have been no need; but his special business and delight was to cut the ropes, or “soams,” by which the poor little assistant putters (sometimes girls) used then to be yoked to the wooden trams for drawing the corves of coal from the face of the workings out to the cranes. It was no uncommon thing in the mornings, when the men went down to work, for them to find that Cutty Soams had been busy during the night, and that every pair of rope traces in the colliery had been cut to pieces. But no one ever, by any chance, saw the foul fiend. By many he was supposed to be the ghost of some of the poor fellows who had been killed in the pit at one time or other, and who came to warn his old marrows of some misfortune that was going to happen, so that they might put on their clothes and go home. Pits were laid idle many a day in the olden times through this cause alone. Cool-headed sceptics, who maintained that the cutting of the soams, instead of being the work of an evil spirit whom nobody had ever seen or could see, was that of some designing scoundrel.

As these mysterious soam-cuttines, at a particular pit in Northumberland, in the neighbourhood of Callington, never occurred when the men were on the day shift, suspicion fell on one of the deputies, named Nelson, whose turn to be on the night shift it always happened to be when there was any prank played of the kind. It was his duty to visit the cranes before the lads went down, and see that all things were in proper order, and it was he who usually made the discovery that the ropes had been cut. Having been openly accused of the deed by another man, his rival for the hand of a daughter of the overman of the pit, Nelson, it would appear, resolved to compass his competitor’s death by secretly cutting, all but a single strand, the rope by which his intended victim was about to descend to the bottom. Owing to some cause or other the person whose destruction was thus designed was not the first to go down the pit that morning, but other two men, the under viewer and overman, went first. The consequence was that the rope broke with their weight the moment they swung themselves upon it, and they were precipitated down the shaft and dashed to pieces.

As a climax to this horrid catastrophe, the pit fired a few days afterwards, and tradition has it that Nelson was killed by the afte damp. Cutty Soams Colliery, as it had come to be nicknamed, never worked another day. To be sure, it was well-nigh exhausted of workable coal; but whether that had been so or not, not a man could have been induced to enter it, or wield a pick in it, owing to its evil repute.

So the owners, to make the best of a bad job, engaged some hardy fellows to bring the rails, trams, rolleys, and other valuable plant out of the doomed pit, a task which occupied them several weeks, and then its mouth was filled up. The men removed to other collieries, and the deserted pit row soon fell into ruins. Even the bare walls have long since disappeared. There is nothing left now to mark the site of the village, if we may believe our authority, Mr. W. P. Shield, ” but a huge heap of rubbish overgrown with rank weeds and fern bushes.”

As for old Cutty Soams, he now finds no one to believe in his ever having existed, far less in his still existing or haunting any pit from Scremerston to West Auckland.

Vol 3 – No. 25 – March 1889 – The Victoria Hall Disaster, Sunderland

STANDING on the terrace in front of the Winter Garden, Sunderland, the spectator will note that one of the most striking buildings in sight is the Victoria Hall. It was here that the sad and never-to-be-forgotten calamity occurred on the 16th of June, 1883, when no fewer than 183 unfortunate children lost their lives.

A public performer named Fay had issued notices in the early part of the week to the effect that he would give a grand juvenile entertainment at the hall on the Saturday afternoon; and, as a means of securing a good attendance, he circulated tickets admitting children at the reduced price of one penny each to the gallery. He likewise announced that prizes, in the shape of books, playthings, etc., would be distributed at the close of the performance. The entertainment commenced at three o’clock, when there were about eight hundred children in the body of the hall, eleven hundred in the gallery, and a few in the dress circle, which was otherwise empty. There were scarcely any adults present besides Mr. Fay and his assistants, only a few nursemaids accompanying such of the children as had paid the full price of admission and got accommodated in the better parts of the house. All went on well until the close of the proceedings, when the entertainers began to distribute prizes to the children downstairs. But as soon as those who were crowded together in the gallery, without any grown-up person to keep them in order, saw that the presents were being scattered about down below, they naturally became excited, and began to fear that none would be left for them. In an instant a number of the children rose to their feet, and made their way to the folding doors leading to the staircase, their intention being to run down into the body of the hall and share in the distribution of the toys.

About three parts of the way down the winding staircase was a door which opened inwards. This door had for some unexplained reason, or perhaps quite accidentally, been fastened partly open by a bolt in the floor, leaving for egress a width of about two feet only barely sufficient for one person to pass at a time. The foremost of the eager youngsters dashed impetuously through the folding doors, and swept in a living torrent down the first two flights of stairs. So long as the way was lighted and clear they passed on safely enough, until, streaming down from, landing to landing, and passing the doors and windows of the dress circle into the corridor, they approached the doorway above mentioned. The winding stair prevented those who were rushing down, with all the eagerness of children in a hurry to participate in the fun, from seeing what was actually happening in their immediate front. Those who were in advance were pushed forwards to the door by the crowd behind them, without the possibility of resisting the pressure. The narrow exit between the half open door and the door-frame was speedily choked up, one spectator averring that he saw nearly twenty of the poor little creatures one above another struggling to get out; and as the rush was still coming incessantly down like an avalanche from a mountain side, the children in front had not the least chance of escape. Some fell against the door; others were forced upon them by the pressure behind; and the lower part of the staircase was filled in an instant of time with a heap of helpless children whom it was physically impossible to rescue or relieve. Those who were still rushing down the stairs in tumultuous haste, cheering as they came on, and struggling who should be foremost, had no idea of what was going on below. So, quicker than one can tell, a dense pile of bodies was crushed in the fatal trap, between the door and the wall, such being the amount of pressure to which the frames of the hapless little ones were subjected that the strong wrought-iron bolt, whose presence did the mischief, was bent by the force of the compact of the shrieking and struggling mass of humanity, literally heaped up in tiers.

It was evident that before the life was crushed out of them they struggled desperately; for when the death-bolt was at length raised, after the bodies of the dead and the dying had been extricated, and the living had been hurried away from the appalling scene, the landing and the flight of stairs leading down to it were seen to be covered with pitiful evidences of the tragedy. Little caps and bonnets, torn and trampled, were lying all over the place ; buttons and fragments of clothing littered the floor ; here lay the fragment of blue ribbon which had tied up some little girl’s hair; there lay a child’s garter ; on another spot the sole of a little boy’s boot torn from the “uppers,” furnishing mute but significant evidence of the violence of the death struggle.

The caretaker of the hall, Mr. Frederick Graham, was the first who became aware that something dreadful had happened. When he got to the lobby, at the foot of the gallery stairs, he found a number of children lying there. After he had got them cleared out with no small difficulty, he proceeded from the outside towards the fatal door, being attracted thither by the groans and cries of such of the sufferers as were still alive. Mr. Graham at once perceived that the bolt had caught in such a way that the door could neither be opened nor shut entirely, and through the aperture, about two feet wide, thus formed, he caught sight of a writhing mass of human forms. He made one frenzied but futile effort to force back the door, and then rushed upstairs by another way into the dress circle, from which position by strenuous efforts he succeeded in stopping the further flow of children to the staircase. He then hurried back to the door, when he saw at once that the only means of rescue was to pull the bodies one by one through the aperture. With the assistance of a gentleman named Raine, a railway clerk named Thompson, and a police constable named Bewick, he commenced the ghastly task. Further help fortunately soon arrived in the person of Dr. Waterston and others. As soon as a body was pulled out, it was rapidly examined, and, if dead, laid out in the area or dress circle; while if the little sufferer still lived (and the signs of vitality were often very difficult to detect), the child was at once conveyed to the Palatine Hotel, the Infirmary, or some other house in the neighbourhood, where Drs. Beattie, Dixon, Murphy, Welford, Lambert, Harris, and other medical men, who were promptly on the spot, devoted themselves ungrudgingly to the work of mercy. The conduct of the cabmen of the town was also beyond all praise. They flocked to the hall with their vehicles, and rendered valuable help in conveying the injured to the Infirmary and elsewhere.

Meanwhile, the dreadful news had spread like wild fire through the town, and the hall was soon besieged by thousands. The excitement was indescribable mothers screaming for their children, and fathers fiercely striving to force their way into the building. It was, however, deemed prudent not to admit anyone until the work of rescue had been completed; but the gentlemen, all of them full of sympathy and compassion, who volunteered to assist in the necessary but thankless work of keeping back the excited crowds, found it a most difficult task. When, at length, those claiming to be the parents of missing children were admitted in batches to the area and dress circle, the scene inside baffled all description. The children were laid out in rows, terrible to behold, many with blackened faces, swollen cheeks, and parched lips. As parents identified their children, their shrieks were most distressing. In some cases they fell upon their dead children, clasped them in their arms, and cried aloud over their dear ones. In many instances the mothers swooned away, and had to be carried to one side, where others, whose children had escaped, sought to restore and console them. One affecting case was that of a poor woman whom Mr. Errington, a member of the Town Council, was sympathetically assisting in her search. As she accidentally touched a corpse with her dress, a man said to her, perhaps somewhat roughly, “Don’t stand upon them,” when she replied, “Good God ! I have too many of my own to stand upon them.” The unfortunate woman, a few minutes afterwards, discovered three of her own children amongst the dead! Another instance is related of a man who, with his wife, pushed his way into the hall, and eagerly scanned the faces of the dead. Without betraying any emotion, he said, with his finger pointed and with face blanched, “That’s one”. Passing on a few yards further between the rows of little ones, he said, still pointing with his finger, “That’s another.” Then, continuing his walk till he came to the last child in the row, he exclaimed, as he recognised the third little one, ” My God! all my family gone.”

Among the many distressing features in connection with the affair, that of mistaken identity was not the least agonising. A number of children taken away in the excitement of the moment were afterwards returned to the hall, the poor people having been misled as to the identity of the shapeless little masses of humanity. In one case, a parent took home a little boy by mistake, and after arriving there found it was the body of a neighbour’s child. Meantime, his own boy had been recovered alive, and was treated with all skill and care possible, though the little fellow died subsequently from his injuries.

The victims of the disaster comprised 69 girls and 114 boys. It was found by analysis that the greatest number were between the ages of 7 and 8 years. The following shows the numbers and ages:

| Ages | 14 | 13 | 12 | 11 | 10 | 9 | 8 | 7 | 6 | 5 | 4 | 3 |

| Victims | 1 | 1 | 6 | 13 | 26 | 23 | 37 | 36 | 19 | 14 | 5 | 2 |

In some families the whole of the children were swept away, and there are known cases where the brokenhearted parents have gone to their last home, never having recovered from the shock.

The disaster was the subject of talk and comment in every household in the land for more than the proverbial nine days; and for many and many a year to come it will remain in the memories of fathers and mothers as the most lamentable event in their lives. But it evoked, too, a spontaneous and noble outburst of humane sentiment, as is always the case when the heart of the community is touched. Money poured in from all sides, and a sum was subscribed for which there was no immediate direct need, as no bread-winners had been lost. Out of the amount promised, nearly 5,000 was received, and with this the expenses of most of the funerals were paid; but unfortunate dissensions hindered the remainder from being put to use for building and endowing a Convalescent Home for Children, as at first intended; and, with the exception of the sum paid for the statue in commemoration of the event, which has now found a resting place in the People’s Park, it still remains unappropriated.

The view of the exterior of Victoria Hall is taken from a photograph by Mr. Paul Stabler, of Sunderland; that of the interior is from a sketch by our own artist. The sketch of the staircase where the disaster occurred is from a drawing by Mr. Robert Jobling. Our other sketches show the Laura Street entrance to the hall, and the fatal door with the bolt in the socket. We also give sketches of the memorial group, and of the group in its glass case, erected in Sunderland Park.

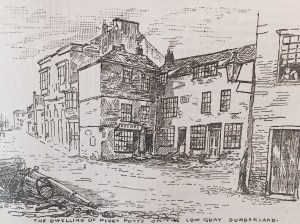

Vol 2 – No. 14 – April 1888 – Peggy Potts

MARGARET POTTS, better known as “Peggy Potts,” who, for many years, was one of the principal public characters of the town of Sunderland, died on Sunday, the 10th October, 1875, in a house in Aikenhead Square, on the Low Quay, aged eighty-six. So at least says her obituary in the local paper ; but it is commonly believed that she died in the workhouse. Peggy was a true “daughter of the soil,” for she had lived in the town all her life. Her maiden name was Havelock, and she was second cousin to the celebrated General Havelock, the hero of Lucknow, her father — a sailor, and afterwards a fisherman having been full cousin to the general’s father. Peggy’s husband, who predeceased her by several years, was likewise a fisherman, and latterly a pilot, and he had the reputation of being a somewhat lazy fellow, who was glad to supplement his gains by those of his more energetic wife. However this may have been, Peggy managed to make a “good fend” for herself. That she was eccentric goes without saying, as the phrase is; but her eccentricity took a practical turn, which not only furthered her own ends in making a livelihood, but made her a universal favourite wherever she went. She was wonderfully ready-witted; and her command of the Sunderland vernacular, which she never dreamt of spoiling by any sort of refinement, was so perfect as to give a zest to every word she uttered.

Those who knew Peggy in her youth testified that she was a very handsome, well-favoured, buxom lass; and she retained to the last the traces of having been so. She was of middle stature, and rather stout. Her dress latterly, when attending to her usual vocation, was a blue bedgown, a flannel petticoat of the same colour, an old fashioned black silk bonnet that set off her comely face to advantage, a silk handkerchief round her neck, and a snow white apron. She was always remarkably clean — “as clean as a pin.”

For many years she made a living by selling fish and other things, and for some time she had a small shop in the Market, where, on Saturdays, she sold cheese. Her custom was to go to the wholesale establishment of Messrs. Joshua Wilson and Brothers, and there buy a quantity of stale cheese, which they let her have at a very cheap rate, as they could not sell it to their regular customers, though it was often of the finest and richest quality. This cheese she would sell at 4d. per pound when it was selling at l0d. in the shops, and good “peg” cheese she would let her friends have for 2d. per pound. One day a friend of the writers went to her stall, when she addressed him thus:— “Noo, then, hoo are ye the morin!” The reply being, “I am very bad i’ my stomach,” she instantly rejoined, “Eat a bit rotten cheese, hunny. Aa had a bit mesel this morin’, an’ aa’m nicely noo. Thor’s nowt like a bit o’ rotten cheese for mendin’ the stomach.”

In the old palmy days of contraband trade, Peggy is said to have turned over hundreds of pounds in the smuggling line. She had her regular customers whom she supplied with goods that had never paid toll to the Imperial Revenue; and no one could more deftly than Peggy outwit the custom-house officers, however keen on the scent. Also, when contraband stuff was not forthcoming, Peggy would go to old Solomon Chapman’s and get a temporary supply (of course along with a permit), and go round and dispose of it as smuggled.

Once upon a time, when she was tramping into the country with a small keg of whisky to serve a friend, she was met by an officer, who guessing what it was she carried, made her turn back, meaning to take her before his superiors. She went along quietly for a good way, when she begged the officer to walk forward a bit. He did so. No sooner was his back turned than she emptied the keg, re-filled it with water, and walked on quickly with it after the officer, on reaching whom she transferred it to his custody, telling him she was tired of carrying it. On arriving at the custom-house, the keg was found to contain nothing but the pure element. The laugh was turned against the officer, and Peggy came off chuckling.

Another time, when there was an uncommon scarcity of fish, owing to a continuance of rough weather preventing the fishermen from getting to sea, Peggy was passing along the sands in company with a friend, when they found a dead codling which had been washed off the rocks. She eagerly seized on it as a prize, and said she would make a good penny out of it. “Why, it’s not fresh,” said her friend. “That’s nowt,” replied Peggy; “aa’ll tyek it up to General Beckwith’s, an’ the hoosekeeper ‘ll jump at it. The cyuk can syeun makk’t aall reet. ” So saying, she lost no time in walking up to Silksworth, only calling at a butcher’s shop by the way, and daubing over the gills with blood, so as to give it a fresh look. The bait took, and Peggy pocketed a good price.

Peggy’s ready wit was unfailing. It was truly redolent of the place. Once in a rencontre with the late Mr. David Johnasson, when he treated her rather gruffly, she told him very sententiously that “London was ruled by Jarmins, and Sunderland by Jews, but still they were not te forget that they wor foreigners!”

A story is current that she once got into trouble through imputing incontinency to a woman of quality for which she was served with a citation from the Consistory Court of the Bishop of Durham, which she not only treated with contempt, but actually burnt. These ecclesiastical courts, however, were not to be defied with impunity, and Peggy, so it is said, was forthwith delivered over to the secular arm, lying for eighteen weeks in Durham Gaol, until released by the interposition of the good Rector Grey, whose memory is still green in Sunderland for his many acts of charity and mercy.

On the Saturday after the death of Henry Esmond, a well-known street preacher, who was a hunchbacked little man, with legs seemingly too long for his body, Peggy, meeting with an acquaintance, a member of the Methodist body, broke out characteristically with — ” Thoo’ll hev hard o’ powr Henry Esmond’s deeth, hunny. Aye, hunny, there’ll be a cruickt angel i’ hiven te-day.” Her belief in the immediate transmission of idiosyncrasies, both of body and mind, to the regions, whether of bliss or woe, beyond the grave, was as full and implicit as in the existence of the sun and moon.

Peggy had a characteristic way of expressing her dislikes. “Aa’ve hed a dream,” said she once, “a fearfu’ dream. Aa thowt aa wes in hell, an’ saw Boney there; an’ aa wasn’t surprised at that. An’ aa saw a lot o’ mair folks besides him, that aa knaa’d or disna knaa — aall bad rascals; an’ aa wasna surprised at that. But aa was surprised when aa saw Mr. Peters there!” Mr. Peters was Rector of Sunderland.

On the morning when the news arrived of the death of the Duke of Wellington, Peggy entered the shop of Mr. John Hills, grocer, High Street, when, finding that gentleman absent, she entered into a jocular conversation with the shop assistants. “Aa’ve some bonny dowters,” said she. “Aa wish some o’ ye wad come doon an’ look at them. Aa’m sure they’ll myek good wives, if they only get canny, decent men.” While thus speaking, in came Mr. Hills, who was a very sedate, solemn, and strictly religious man. Instantly Peggy changed her tune. “Aa wus just sayin’ te yor lads,” she observed, “that Satan ‘ll hev a bonny job in hand te-day. The Dyeuk o’ Wellin’ton’s deed, an’ ne doot gyen doon belaw; an’ whatll be the upshot when he meets wi’ Boney? Aa doot the Aad Yen ‘ll ha’ to get iron cyages myed for them, te shut them up in, an’ keep them from teerin’ each other’s thrapples oot.”

Peggy was an early riser, and never was off her feet from sunrise to sunset. Here is the way in which she used to arouse laggards in cases when, as after a storm on the coast, valuable things were to be had for the picking up — first come first served (the reference is to a man named Billy Peacock, a fishmonger of her acquaintance) :— “Billy, get up, ye greet lyeazy beast! What are ye lyin’ snoozin’ an’ snorin’ there for? There’s coals i’ the Bight as big as byesins ! Get up, an’ take yor share o’ them.”

She was frequently before the magistrates, but in most cases rather in the character of an informant or witness than as a misdemeanant. Many were the scenes enacted in the police court which derived their chief attraction from her unrestrained self-confidence and mother wit “What’s your husband ?” asked Mr. Joseph Simpson (vulgarly called Joe) one day, when she appeared before him. “A pilot,” was the answer. “How long has he been a pilot?” ” Ever since he was as big as a lobster,” shouted Peggy. When a new magistrate came to sit on the bench, Peggy would say, “Aye, Mr.________ , hunny, aa knaa’d yor father, an’ he was a daycent man; the best wish aa can wish ye is that ye may come up te him.”

Her name was once taken in vain by the editor of a local paper, who, on the occasion of two solicitors’ wives having a quarrel and a match at fisticuffs and eye scratching, took the liberty to say the melee was “worthy of Peggy Potts.” On hearing this, the irate fish woman hastened to the newspaper office, and demanded to see the editor. “Bring him oot te me,” said she, “an aa’ll suen give him a settlin’. The impident rascal, te compare me tiv onny o’ yer Brumagum ladies. Aall let him knaa whose nyem he’s been tyekin liberties wi’. Bring him oot, therecklies.” “But he’s engaged, Peggy,” said the man in the office, “and you cannot see him just now.” “Aa must see him, though,” replied the virago, “an’ see him aa will” “If you mean to prosecute us for a libel,” said the cleric, “you should send your attorney.” “Them’s my ‘tornies, sor,” shouted Peggy, brandishing her ten fingers, armed with good long nails. But after some further parley, she was sent away pacified, only declaring that she reckoned it a perfect disgrace to be likened to two such upsetting trash as the belligerent solicitors’ wives.

Peggy’s favourite seat on a fine summer’s night was the steps of the Rendezvous, next door to where she lived. Here she knitted stockings and gossiped with her neighbours. This Rendezvous was formerly the quarters of the Press Gang, and the captives used to be conveyed secretly away through passages and stairs in the rear up to the High Street.

She was naturally very proud of her relationship to General Havelock. Speaking of him she would say: — “Ye knaa he’s yen of wor family.” When introducing herself to strangers, it was her habit to say she was “Margaret Havelock, cuzzin te the greet general.” She was fond of airing her grievances in not having been rightly treated in respect to pecuniary matters by her blood relations; and she often interviewed the officers at the Barracks for the purpose of detailing, in her characteristic way, the peculiar claims which she thought she had on the consideration of the higher powers. In her old age, she still retained the lines and traces of the beauty of her younger days, and that not without a certain air of determination in her countenance, accompanied, as some one has said, “with a promptness, decision, and energy in her actions which might serve to help those who saw the Havelock in a bed-gown and blue skirt to form some idea of the Havelock in tartan trews.”

The Sunderland lads used to annoy the old lady in her latter years by shouting after her —

“Peggy Potts sent to jail,

Selling fish without a tail”

Holding up a large gully to her tormentors, Peggy would exclaim— “If aa ony could catch ye, aa wad cut yer throat frae ear te ear, ye scoundrels.”

Peggy was a great favourite with the distinguished strangers who visited Sunderland from time to time, as well as with the most respectable of the town’s folks, who were uniformly courteous and kind to her, and most of whom could enter heartily into the humour of the genial old woman. George Hudson, the Railway King, might be seen walking arm-in-arm with her at election times; and she was always one of the foremost women in Sunderland to take off the men’s shoes on Easter Monday. The following paragraph, cut from an old Sunderland Times, will illustrate this curious custom: — “The fisherwomen of Sunderland, having ascertained that Mr. Hudson would arrive at Sunderland on Easter Monday, determined that the hon. member should ‘ pay for his shoes’; and accordingly a party of them proceeded to Brockley Whins, where, on the hon. gentleman changing carriages, he was at once pounced upon, and told that he could not enter the railway carriage until he had complied with the ancient custom. Having done so with his accustomed munificence (50s.), he was allowed to proceed. On his arrival at Monkwearmounth, another batch, headed by the redoubtable Peggy Potts, not aware that they had been outwitted, were found in waiting; and, much disappointed, gave vent to loud denunciations at being so cleverly ‘done’ by the nine adroit members of the sisterhood of fisherwomen who had proceeded to Brockley Whins, and who, we must not omit to mention, rode home in first-class carriages, highly elated with their success.”

A few years before her death, Peggy was removed to the workhouse. She was very indignant that the Queen should let the cousin of Greneral Havelock go to such a place. The matron of the workhouse, in assigning her a dormitory, had to place her in the bed next the door, the room being full; and Peggy complained bitterly next day of the draught she felt, and demanded to have her bed changed. But when the matron pointed out the state of the case, and asked her, “Whose bed must I take to put you in ?” the poor woman saw the force of the appeal, and resigned herself to her fate.

One day, a well-known doctor in the town met Peggy when she had got leave to be out, and she began to entertain him with heavy complaints as to the hardships of workhouse life. And on his manifesting some impatience to get away, she said: “Oh, doctor, hunny, could thoo give us thrippence to get a little bit o’ tea; for tea, thoo knaas, is the staff o’ life to a poor aad body like me.” The money was, of course, freely disbursed, and the doctor proceeded to make his calls. But, on his return, he saw Peggy coming out of a public-house. “Ah, Peggy, “said he, “I thought you told me that tea was the staff of life.” “Wey, se it is, hunny,” answered Peggy “but thoo knaas whisky’s life itsel”

A clever young Sunderland artist — Mr. J. Gillis Brown, jun.— has contributed the sketches which accompany this article.

William Brookie

Vol 1 – No.6 – August 1887 – Sunderland Lighthouse

A triumph of engineering skill was accomplished in Sunderland when the lighthouse at that port was bodily removed from one end of the pier to the other. The former site, which was on the old pier, had become much impaired, and the new pier having been extended considerably to the east, it was deemed desirable that the lighthouse should stand as near the new pier end as possible. It was at first intended to take down the lighthouse and rebuild it; but Mr. John Murray, the engineer under whose direction this extraordinary effort was performed, proposed to remove it entire. As a proof of the feasibility of the plan, it was stated that houses in New York had been removed from their original situation to a considerable distance without sustaining any injury whatever; that the immense block of granite forming the pedestal of the statue of Peter the Great, at St. Petersburg, was conveyed four miles by land and thirteen by water; and that obelisks had also been transmitted from Egypt to Europe. The removal of Sunderland Lighthouse, however, was considered a more dangerous undertaking, from the circumstance of its being composed of stones of comparatively small dimensions, as well as from its great height and small base. The arrangements suggested by Mr. Murray were: “That the stone work at the base, which is 15 feet in breadth, should be cut in detached parts, and timbers introduced so as to form an artificial base, and which should also act as a mooring carriage to consist of eight Memel baulks, beneath which other baulks should be laid with iron rails forming a railway. Each baulk of the carriage rested on 14 iron wheels, and from the extremities of the carriage on all sides large timber stays were erected, so ad to support the body and top of the building.” The building had to be drawn about 30 feet to the north, and 420 feet to the east, by powerful screws, along a railway, on the principle of Morton’s patent slip for the repairing of vessels. The necessary preparations having been effected, the work of removal was first taken several yards in a north-easterly direction. Rails were laid to convey it forward to the easterly extremity of the pier. During the week commencing with Monday, the 14th of September, 1841, the lighthouse was moved daily more than 30 feet in about as many minutes, including stoppages; but whilst actually moving it went at the rate of about two feet in a minute. Whilst the work was proceeding the screws were abandoned, and the building was drawn forward on the railway by ropes affixed to three windlasses, thirty men being engaged in this part of the work. The line of way was laid on a curve in order to bring the reflector round to a due east position. Much of the time occupied in the process was engaged in shifting the ways, which could not be laid the whole extent at one time. The movement process was completed on Monday, the 4th of October, by the building being brought up to the site on which it was to be fixed. “The event,” says a writer in the Weekly Chronicle of that date, “was witnessed by a number of ladies and gentlemen who had assembled on the occasion, and who united with the workmen in loud and enthusiastic cheers of congratulation to Mr. Murray. ” It is remarkable that not a single accident occurred to anyone during the progress of the work, and that the building did not sustain the slightest injury by its removal. The light was exhibited every night by gas, as usual, so that not the least inconvenience resulted from the removal, which undoubtedly would have been the case had the entire building been pulled down for the purpose of re-erection. Our illustration shows the lighthouse as it appeared during the process of removal.

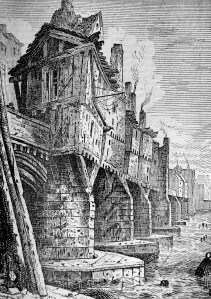

Vol 1 – No. 1 – March 1887 – Old Tyne Bridge

As at recent Exhibitions at South Kensington and Edinburgh the ghosts of “Old London” and “Auld Reekie” revisited the glimpses of the moon, so, on Newcastle Town Moor next May, when the Royal Jubilee Exhibition opens, we may expect to find the ” counterfeit presentment” of Old Tyne Bridge spanning the still waters of Lodge’s Reservoir, or what is left of it, as the original did the swirling stream of coaly Tyne in days gone by. It will be a notable and a cheering spectacle in the eyes of those of antiquarian taste, as affording a rare example of what Mackenzie calls the ” improving spirit of the age” diverted from its usual channel of destruction into the opposite one, the revival of old things It would perhaps have been going too far back to have attempted to show the similitude of the Roman bridge of A.D. 120, which Hadrian threw across the Tyne, and which, as far as we know, though doubtless with many patchings and repairings, seems to have lasted for 1,130 years. But in the reproduction of the edifice which succeeded this and lasted up to 1771, we can look with more sympathising eyes, as being nearer our own epoch, and we may say almost linked to it by memory; for are there not men now living who have known and conversed with those who were familiar with, and perhaps even lived on, Old Tyne Bridge? The original and its copy are, in a certain way, linked together by a curious coincidence; for the one was erected during the reign of the first English monarch who saw the jubilee year of his accession, as the other will be, if all goes well, during the reign of the last who has enjoyed a similar rare experience. It was in 1250, in the reign of Henry III., that Old Tyne Bridge was built of stone, on the site of its predecessor, which, as recorded by Matthew Paris, was destroyed by fire in 1248. What a wealth of romantic incident and historic association is there not bound up with the story of the old bridge which stretched across the Tyne, and formed part of the high road between North and South for over five hundred years commencing on the eve of the summoning of England’s first representative Parliament, and ending on the eve of the American War of Independence! When we look on its restored form, what pictures could not be conjured up from the dark recesses of the past of the structure and its fortunes and changes, and of the succeeding generations which have in turn passed over it and out of ken, save for the glimpses we catch of them now and again by the faint and uncertain light of the torch of history! The bridge itself we may see, in our mind’s eye, in process of evolution into a hanging street houses being added and extended, altered and rebuilt, as the years passed on. We may see the massive tower near the centre, with its portcullis and frowning arch, degenerating from a military work into a house of detention for thieves and vagabonds. We may see its lonely hermit in his cell, praying, as enjoined, for the soul of that Newcastle worthy of worthies, old Roger Thornton. We may see the gateway built at the south end, where was once a drawbridge, and the rising of the magazine gate at the north end, where was set up by loyal hands and pulled down by the Parliamentarians the statue of King James I., and where, after the Restoration, was placed the statue of the Merry Monarch now to be seen in our Guildhall. We may see, too, on occasion, spectacles gruesome enough in all conscience, evidences of barbarous ages at one time the severed right arm of Scotland’s betrayed champion, Sir William Wallace, displayed upon the battlement of the Bridge Tower : at another, and that as late as the reign of Elizabeth, the head of Edward Waterson, a seminary priest who suffered in Newcastle, elevated on a spike on the same place ; many a time and oft such common sights as the heads of a few Tynedale mosstroopers bleaching there in the wind and rain ” for the encouragement of the others.” But we may see a more cheering sight the gorgeous pageant of the nuptial procession of Margaret of England, daughter of Henry VII., pass over the bridge on its way north, where the fair princess was to wed the King of Scots who afterwards fell on Flodden Field. We may, still in imagination, hear the doleful scream of that poor servant maid of Dr. James Oliphant, who, one mid day in 1764, leaped from her master’s cellar window, to find her death in the deep waters of the Tyne. (The four-storey house of Dr. Oliphant stood over the southernmost arch of the bridge the cellar, so called, hanging below the arch, its floor very little above the level of the stream.) We may see the changing crowds passing and re-passing along the narrow roadway of the bridge, with the timbered houses towering high above and almost meeting overhead. We may see them stopping, perhaps, to cheapen the goods in the shops milliners’, mercers’, hardwaremen’s, booksellers’, cheesemongers’ which line the bridge on either side. We may see, perchance, the fire which destroyed the shop of “upright, downright, honest” Martin Bryson, bookseller, and friend of Allan Ramsay. And, last scene of all, we may see the destruction of the whole quaint fabric in 1771. On Saturday morning, the 16th of November in that year, the bridge stood perfect, presenting the aspect we see in the copy of an etching by T. M. Richardson, sen., made from an ideal sketch by his son George. At night, the river, swollen by the recent rains in the west country, rose to an extraordinary height, and, as darkness fell, was heard rushing with fierce violence through the arches, so that the bridge quivered and shook in an alarming way. Before daybreak next morning Old Tyne Bridge was no more. The story of its fall, of the tragic fate of some of its dwellers, and of the exciting adventures of others fortunate enough to escape, has often been told. The other view we give, which is taken from a plate in Brand’s “History of Newcastle,” will convey some idea of the ruins as they appeared a few days after the catastrophe. Soon a sturdy successor arose from the ruins the Tyne Bridge which most of us remember well, and which was replaced in 1876 by the present Swing Bridge.

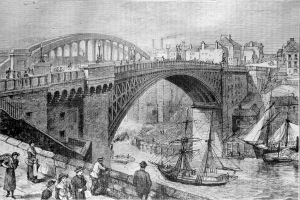

Vol 5 – No. 48 – February 1891 – Sunderland Bridge

The Monthly Chronicle for November, 1887 contained an account of the bridge over the Wear at Sunderland which was constructed and erected by Rowland Burdon in the year 1796. The total cost of the structure was 40,000. Of this sum 30,000 was advanced by Mr. Burdon, at 5 per cent, interest, on security of tolls, while the remaining fourth was raised by subscription on loan. Owing to adverse pecuniary circumstances, the shares held by Mr. Burdon were afterwards offered for sale. As there was no prospect of realising by this means, it was determined to sell Mr. Burdon’s interest in the bridge by means of a lottery. All the circumstances in connecion therewith are fully detailed in the Monthly Chronicle for June, 1889, p. 254. The foundation stone of Sunderland Bridge was laid on September 18, 1795, the bridge being opened to the public on August 8, 1796. An Act of Parliament was obtained in 1857 for the renovation of the bridge, which was carried out under the superintendence of Robert Stephenson. An additional interest is attached to the drawing which we now present to our readers from the fact that it includes a view of the railway bridge which also spans the Wear.

New Facebook Page!

Hello,

Wow, I’m bowled over by the response to this blog! I started two days ago and almost 300 people have viewed the blog from ten different countries! I really can’t take any credit for it. I’m just the monkey sharing these brilliant stories, written over 125 years ago, as it just feels right that they should be shared. I really hope you enjoy reading them.

Just to help spread the word I have set up a facebook page to so please feel free to like it, share it and leave comments. If you have never read any of these books they cover a huge variation of places and subjects so if you have any requests for stories from a particular area (obviously in the Northeast) please let me know and I will see if there is anything close. So please come and check it out here https://www.facebook.com/northeastlore

I am also on twitter @jpmorton82 so please feel free to get in touch!