Sir, said Dr. Johnson, “let us take a walk down Fleet Street” We propose to our readers a walk up Pilgrim Street. We shall find “much matter” as we journey up the gentle hill, “the longest and fairest street in the town,” according to William Gray, whose “Chorographia” was printed in 1649.

This street, still one of the most interesting in the town, derives its name from the pilgrims who lodged in it when on their way from all parts of the kingdom to worship at Our Lady’s Chapel at Jesmond. The founders of the chapel are unknown, but we know that it was in existence in 1351, for then we find Sir Alexander de Hilton and Matilda, his wife, presenting the chaplainship to Sir William de Heighington, who shortly after resigned it, believing he had no right or title to it. In Edward VI.’s time, the Corporation obtained possession of the chapel, and forthwith sold it to Sir John Brandling. In olden days, pilgrims trooped to it from all parts of the kingdom. Such pilgrimages were popular in the early middle ages. For illustration, we may point to the will of William Ecopp, Rector of Heslarton, Yorkshire, who, amongst other things, bequeathed provision for a pilgrim, or pilgrims, to set out immediately after his burial to various shrines, at each of which 4d. was to be offered. The list of places is too long to be quoted in its entirety; but the extent of ground to be covered may be imagined when we find that Canterbury, London, Lincoln, Lancaster, Scarborough, York, “Blessed Mary of Jesmond,” Carlisle, and Galloway, figure therein. (See Mr. R. Welford’s interesting “Newcastle and Gateshead in the 14th and 15th Centuries,” vol i, p. 364). Bourne gravely tells us that the reason the pilgrims took this road was because there was a house of call ready to respond to their wants. “There was an inn in this street which the pilgrims were wont to call at, which occasioned their constant coming up this street, and so it got its name, as the inn did that of Pilgrim’s Inn.” Brand fancies that there were more pilgrim’s inns than one; for, in 1564, mention is made of the execution of one Partrage for coining false money in “the greate innes in Pilgrim Street.” There was, says an old manuscript quoted by Hodgson, a place of sanctuary near the Pilgrim’s Inn; and, according to Bale’s “Life of Hugh of Newcastle,” a famous Franciscan, pilgrims visited also certain relics of St, Francis, preserved in the Grey Friars’ Convent near the head of the street. At present, though, we are only at its foot) with the church of All Hallows, or All Saints, on our right.

With curious eyes must successive pilgrims have gazed on the church, which in the thirteenth century looked down on the stately buildings of the Austin (or Augustine) Friars, the burying-place of the Northumbrian kings, and afterwards “the king’s manor house.” The ancient church first finds mention in 1286. From a painting of it still preserved in the vestry, we can gather an idea of its appearance, which, sooth to say, cannot have been imposing. It was low and very broad, 166 feet by 77, and of Decorated English architecture. The tower was high, and out of proportion to the rest of the church. But as it bore the storms of five centuries, and could not even then be loosened without the aid of gunpowder, its strength was unquestionable. No true Novocastrian can regard with indifference the church of All Hallows, for with it are bound up memories of some of Newcastle’s greatest names. Roger Thornton, Sir Matthew White Ridley, Lord Eldon, Lord Stowell, the Ravensworths, the Collingwoods, Ellison, Brandling, Clavering, W. Blackett, and other persons and families of note are all associated with this ancient (though now restored) parish church. How is this? The present vicar, the Rev. A. S. Wardroper, in his lecture on “All Saints’, the Old and the New,” gives the answer. “In their day, merchants and their families lived where they worked. The wealthy part of the community lived, many of them, in Pilgrim Street. This may be inferred on examining the staircases in Stewart’s Court, or the one over the Eldon Room; the chimney-pieces and oak balustrades in the largest common lodging house; the quaint work on ceilings of rooms over the Bake House Entry; besides the crests over doorways and gateposts in Clayton’s Court, Painter Heugh, and Akenside Hill, in addition to the armorial bearings on the tombstones in the churchyard.” John Wesley generally worshipped in All Hallows when in Newcastle; and in his journal he records that he found more communicants therein than anywhere else in England, save London and Bristol. The sacramental cup handed to him is the same now in use at All Saints’ in the office of Holy Communion. There were seven chantries in All Hallows, adorned with precious stones and other gifts. There were also portraits of benefactors on stained glass. The civil wan swept away all these. In 1780, the old building became shaky; in 1785, its south pillars gave way; in July, 1786, service was celebrated in it for the last time. A new church was resolved upon, and David Stephenson was chosen as architect. The body of the new building was opened in 1789, but the spire was not finished until 1796.

A foolhardy feat signalised the completion of the spire. One John Burdikin, a private in the Cheshire Militia, stood on his head on the round stone at the top of the steeple, and remained in that inverted position for some time, 195 feet above the ground. The man was afterwards a barber in Gateshead. His son, a bricklayer, did the same thing in 1816, when some repairs were in hand. Truly, they did not “set their lives upon a pin’s fee.” The new church of All Saints’ has been condemned by some as unchurchlike; even Mackenzie has a fling at it as “certainly a neat, smart, modem structure, but totally devoid of that solemn religious grandeur which distinguishes the ancient Gothic churches.” Others agree with Thomas Sopwith — no bad authority — in regarding it as “the most splendid architectural ornament in this town, equally conspicuous for the convenience and novelty of its interior arrangements, as for the variety and splendour of its decorations.”

The spire of the church was severely shaken in May, 1884, by a wind-storm which elsewhere left its mark behind it. Divine service was being celebrated in church at the time, which was Sunday morning; and it is a rather curious fact that a very considerable crowd gathered outside to watch the oscillations of the imperilled spire, which seemed likely to topple down at any moment on the devoted heads of the kneeling worshippers beneath it. The service, however, was carried on to its conclusion in seemly and reverent fashion; but the very next day the work of restoration was taken in hand in good earnest. The shattered stones were taken down (some of them are preserved in the church ground now, and are no uninteresting objects); and in time the spire was restored, stronger than ever. By way of commemorating this work, a stone was placed at the summit, bearing this inscription:

“This spire was restored and partly rebuilt, June, 1884. Rev. A. S. Wardroper, vicar; Collingwood F. Jackson, Peter Carr, Thomas Stamp Alder, Thomas Morgan, churchwardens.”

The churchyard has of late years been prettily and becomingly laid out as a flower garden, at the expense of Mr. R. S. Donkin, now a member for Tynemouth. Mr. John Hall has also proved himself a generous friend to the church, presenting it with its dock, and also with a pair of lamps. The latter were formally handed over to the churchwardens by Mr. Joseph Cowen, then member for Newcastle, who delivered an address from the church steps on the occasion, as did also Archdeacon Watkins, who was senior curate at the handsome salary of five shillings a year.

Opposite to the west stairs of the church, Elizabeth Nykson, widow, founded an almshouse about the beginning of the sixteenth century, for the use of the poor of the parish, “on condition of an annual dirge and soul mass being performed in that church.” Four women, who lived in it, were allowed 20s. a year for coals. In Bourne’s time (the beginning of the eighteenth century), the poor inmates had eight chaldrons of coal and 12s. a year; but the house was then “going fast to ruin.”

We now pass Silver Street on our right, leaving it and all the other offshoots of our main road alone for the present, and opposite Painter Heugh are face to face with the fine old house with which Lord Eldon’s name is still associated. John Scott, afterwards Lord Eldon, intended occupying this house, as he at one time expected to be Recorder of Newcastle. Things becoming brighter for him in London, he gave up the idea, and turned over the house to his brother Henry. It must then have been a mansion, indeed; for even in its decadence there are remnants of its ancient beauty.

Note on our left hand that quaint little barber’s shop with its projecting pole. Well, that is, as the notice in the window proclaims, “ye oldeste shaving shop in ye citye.” But it has an interest independent of this fact, for here it was that Tobias Smollett discovered and unearthed the original of his immortal Strap, as related in the Monthly Chronicle, vol. i., page 342.

We are now in the vicinity of some old-fashioned posting houses of the past; the Fox and Lamb, described by Mackenzie as in his day (his history was published in 1827) “a respectable, well-frequented inn”; the old Robin Hood, whither William Purvis, better known in his day as “Blind Willy,” was accustomed to journey for his beloved “bonny beer”; the old Queen’s Head; and the Blue Posts. The two latter have been modernised in their internal arrangements; with them indeed “old times are changed, old manners gone.” But our ancestors had their jovial nights there; cakes and ale were plentiful, and ginger hot i’ the mouth too. Thus, at the Blue Poets, the Newcastle Lodge of Free and Easy Johns held its meetings. It was the third lodge of its kind in the kingdom, being preceded only by those of London and Dover. It was first formed in 1778, and could soon boast of more than a thousand members. The association was formed merely for convivial purposes; but there was a ceremony of initiation, a grip, a password, and so forth. In August, 1784, Charles Brandling, then one of the members for the borough, presented the lodge with a large silver goblet, on which his arms were engraved, with a suitable inscription.

We now pass the new City Road, Mosley Street, and the Arcade — the latter associated with the grim tragedy of 1830, for which Archibald Bolam received transportation for life, being found guilty of the manslaughter of the bank-clerk, Millie, under circumstances which excited profound attention at the time, and suggested the gravest doubts as to the moral character of the murderer; for so he was generally regarded. And next we come to Pilgrim Street with its dean face on; its rags and tatters we have now pretty well turned our backs on. On our left hand is the George Inn — in Mackenzie’s time, “a travellers’ house, and often used for bankrupt meetings.” A little above is the Queen’s Head Inn, at one time the chief posting-house in the town, now the Liberal Club. Riders and oat-riders, in their showy dresses, have often rested carriages of four and sometimes of six horses here; royalty has feasted herein, and men of mark in the scientific world have here assembled to do honour to kindred worth. Thus in August, 1819, Prince Leopold and his suite arrived here, and in the evening visited the Northumberland Glass House. On the next day, which chanced to be the Assize Sunday, he attended divine service at St. Nicholas’ Church, accompanied by Sir William Scott (Lord Stowell), after which he partook of a collation at the Mansion House, and then set off for Alnwick Castle, to dine with the Duke of Northumberland. “The public,” we are told, “showed him much respect, and he was sainted by the guns of the Castle.” In 1815, there was another royalist demonstration of its kind in front of this same inn. In the June of that year, Count Lynch, Mayor of Bordeaux, who was the first to hoist the White Flag in France, arrived here on his way to visit his relative, John Clavering of Callaly. “The populace,” again says Mackenzie just quoted above, “assembled before the Queen’s Head, and congratulated this Bourbonist with repeated huzzas on the defeat of Bonaparte at Waterloo. “Two years later, in October, 1817, a gathering of a different character took place, John George Lambton in the chair, when a superb service of plate was presented to Sir Humphrey Davy, “for his invaluable discovery of the safety lamp,” by “a numerous company of gentlemen connected with the coal trade.” This meeting, let us remark in passing, did not pass without its counteracting gathering; for, in January, 1818, “a respectable party of gentlemen dined at the Assembly Booms, Newcastle, C. J. Brandling, Esq., in the chair, on the occasion of presenting a piece of plate to Mr. George Stephenson, for the service rendered to science and humanity by the invention of his safety-lamp.”

Nearly opposite the Queen’s Head is the Friends’ Meeting House, a neat, plain, substantial building, bearing on its frontage the date 1698, and presenting a clean and comfortable appearance worthy of “the people of God called Quakers,” as they are designated in a Durham Quarter Sessions document issued in 1689. The passer-by, though, must not suppose that the present building is identical with that of 1698. Not so; that was pulled down in 1805, and the present one built. It was considerably enlarged in 1812. Further up the street, on the same side as the Friends’ Meeting House, are the offices of the Board of Guardians, once the town house of the Peareths of Urpeth.

We come next to the New Police Court. At the head of the steps from the principal door is a very fine stained glass window of Justice, blind, and scales in hand. On the left hand, on. entering from Pilgrim Street, is the Chief Constable’s private office; behind is the office for the detective department, containing some curious illustrations of the tools of those with whom the detectives are at chronic war; and then the office proper, where unfortunates in the hands of the law are “run in,” and forthwith duly charged and caged. Away from this room are the cells, where persons apprehended may be temporarily lodged for the night. In the upper part of the building are resting rooms for the policemen, where they may read the newspapers, indulge in innocent games, and practise the latest breaks and cannons in the noble art of billiards. The sculptured figures on the exterior of the building were executed in Edinburgh.

On the same side as the Police Court is the Conservative Club, previously the residence of Mr. George Hare Philipson (who died there), father of Mr. John Philipson, the head of the well-known coachbuilding firm of Atkinson and Philipson, and of Dr. G. H. Philipson, the eminent physician. The house, a comfortable and substantial one, was originally built by Dr. Askew, who practised in his profession for nearly fifty years in Newcastle with the greatest approbation and success.

By the side of the Conservative Club is the entrance to the celebrated works of Messrs. Atkinson and Philipson, a striking evidence in their way of Newcastle skill, energy, and enterprise. The Atkinsons of the firm have long been dead. Mr. John Philipson is now the sole proprietor. The concern was founded in 1794. Mr. Philipson takes a generous and enthusiastic interest in his business; but it would convey a wrong impression of him altogether to suppose that he has no interest in anything else. On the contrary, long before the City and London Guilds and Gresham College took the subject up, technical education was made a great feature in these works. Hence the establishment has aptly been described as a training school for coachbuilders. A volume on “Harness as It has Been, as It Is, and

as It Should Be,” is from Mr. Philipson’s pen. It met with a very favourable reception when first published. In it war is declared, root and branch, against the bearing rein, as an instrument of torture for that noble but often ill-used animal, the horse.

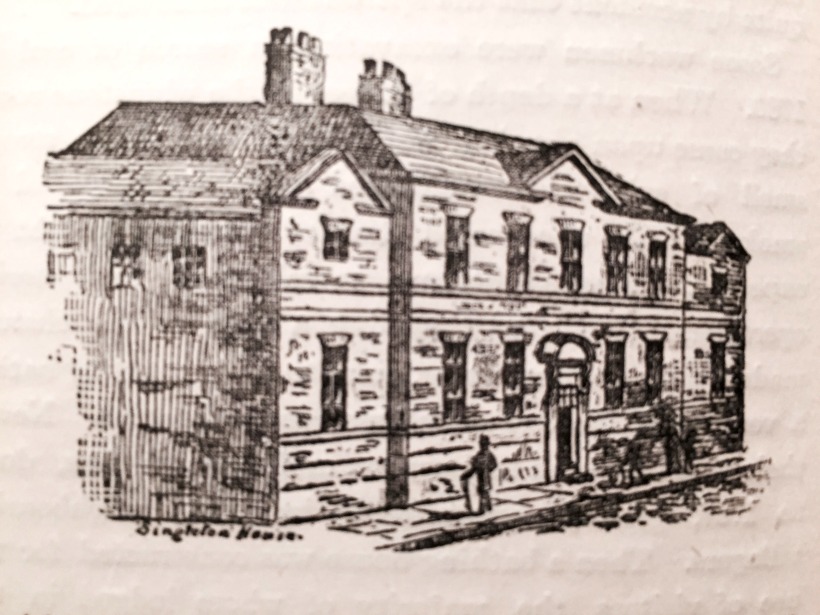

Nearly opposite to the present Conservative Club stood the once celebrated Anderson Place. The building was erected almost on the site of the Franciscan Priory. The Franciscans were divided into two parties — the Conventuals and the Observants. Our Newcastle Franciscans were of the latter persuasion. According to Leland, their house stood by Pandon Gate; “it is a very faire thing.” Mackenzie maintains that this is an obvious mistake, for this reason:— “The site of this monastery must have been somewhere in Major Anderson’s grounds, adjoining the High Friar Chare, which must have conducted to it. The Milburn MS. says it stood near Pilgrim Street Gate. “He goes on to point out that Brand found, built up in the wall of a house adjoining this site, the fragments of a gravestone, with a sword marked on it. Now, this house stood in Pilgrim Street, at the corner of High Friar Lane. This, then, seems to settle the Observant site pretty clearly. Besides that, we have the testimony of an old Pilgrim Street standard. On, or nearly upon, it was a brave mansion built by Robert Anderson, merchant, in 1580. In 1610 it was called the Newe House. Somewhat later it became the headquarters of General Leven during the captivity of Charles I. in Newcastle. There is a popular tradition that the king attempted to escape from this house by the passage of the Lort Burn, a stream which then ran down on the east side of the Sandhill, and that he managed to get as far as the middle of the Side, when he was caught in an attempt to force an iron gate communicating with the sewer. A ship was said to have been in readiness to transport him beyond sea. William Murray projected the scheme, and communicated it to Sir Robert Murray. Somehow the secret became known; and thereafter the king was guarded by soldiers within and without his chamber, who annoyed him much by their continual smoking. He shared his royal father’s antipathies in that respect. The house passed in 1815 to Sir William Blackett, of Matfen, from Sir Francis Anderson. In 1785 it was sold to George Anderson, a wealthy architect, and thence it passed to Major Anderson. A princely house was this Anderson Place, according to Gray; whilst Bourne dilates on its walks and grass plots, its images and trees, its shady avenues and curious and well-painted ceilings.

But now we approach the goal of our sauntering; for here before us, at the head of the street, stood the one formidable Pilgrim Gate, “remarkably strong, clumsy, and gloomy.” In the troublous times of old, it was, doubtless, a valuable means of defence when hostile foes threatened the beleaguered town. But when more peaceful days followed, when the mail-clad soldier no longer clanked through the now peaceful street, it by degrees dawned on the inhabitants that this once valued defence had degenerated into naught better than a public nuisance. Such ideas, however, do not take root in a day or a year. It was felt that the arch was so low as to obstruct the passage of waggons, and that it interfered with the free circulation of the air in the town. But the day of its doom was still distant, even when these opinions more and more made way. The Joiners’ Company had their hall above the gate; wherefore it behoved its worshipful members in 1716 to repair and beautify it, and the old relic of former days obtained respite. In 1771 another attempt was made to reconcile its preservation with the demands of the time; convenient foot-passages were opened out on each side. But these expedients did not answer their purpose, and in 1802 the whole gate was levelled to the ground. A cannon-ball was found in the wall on the occasion of the demolition. It was supposed to have been fired during the siege of Newcastle in 1644, when the gate was nobly defended.

Our sketch of Pilgrim Street Gate is taken from the engraving which appeared in the first volume of Brand’s “History of Newcastle.”