Many centuries back, the Quayside was a fortified place. Before the town walls were built, there can be no doubt that the Danes often enough paid their undesirable visits to the banks of the Tyne. Indeed, tradition hath it that they were accustomed to lie, at such time, at the part of the river known long after their day as Dent’s Hole; that is, the Danes’ Hole; though we now know that Dent’s Hole was named after the local family of Dent, who owned the adjoining manor. Then, later on, we had our good friends the Scots paying us attentions that were sometimes found to be more free than welcome. It was, therefore, only prudent that, when our forefathers were about it, they should defend their town from hostile attacks, even on the water side. But when “old times were changed, old manners gone,” the Quayside section of the town wall was discovered to be an obstacle to the development of trade; and so it came to pass that, in 1763, workmen began to raze it to the ground. After they had knocked down the old wall, they proceeded to divide the east end of the Quay, from Spicer Lane to Sandgate, by iron rails, and to construct a descent to the portion adjoining the river by several steps. This arrangement answered for a while; but, some years after, the roadway was raised and levelled, and so transformed into a fine broad wharf. Since then our Quay has been continuously and watchfully strengthened and improved whenever the occasion seemed to arise for any such treatment.

Many centuries back, the Quayside was a fortified place. Before the town walls were built, there can be no doubt that the Danes often enough paid their undesirable visits to the banks of the Tyne. Indeed, tradition hath it that they were accustomed to lie, at such time, at the part of the river known long after their day as Dent’s Hole; that is, the Danes’ Hole; though we now know that Dent’s Hole was named after the local family of Dent, who owned the adjoining manor. Then, later on, we had our good friends the Scots paying us attentions that were sometimes found to be more free than welcome. It was, therefore, only prudent that, when our forefathers were about it, they should defend their town from hostile attacks, even on the water side. But when “old times were changed, old manners gone,” the Quayside section of the town wall was discovered to be an obstacle to the development of trade; and so it came to pass that, in 1763, workmen began to raze it to the ground. After they had knocked down the old wall, they proceeded to divide the east end of the Quay, from Spicer Lane to Sandgate, by iron rails, and to construct a descent to the portion adjoining the river by several steps. This arrangement answered for a while; but, some years after, the roadway was raised and levelled, and so transformed into a fine broad wharf. Since then our Quay has been continuously and watchfully strengthened and improved whenever the occasion seemed to arise for any such treatment.

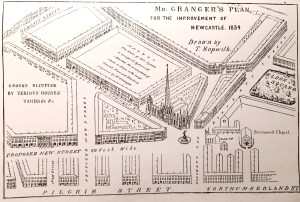

The time was coming when this local Rialto was to receive its baptism of fire. Men of middle age remember that season of trouble and anxiety right well. Those of them at all interested in the Quay in the year 1854 will recollect the quaint, old-fashioned appearance which its buildings then presented. Queerest of them all, perhaps, was the Grey Horse public-house, with its bold projection seeking, and not in vain, to usurp part of the footpath. On the night of the 5th of October in that year, that great fire occurred which has already been described in the Monthly Chronicle. (See vol. ii., p. 549). As in so many matters more, out of this immediate evil came future good. In place of the old chares and time-worn houses and shops thus so decisively destroyed, there arose those handsome stone-fronted buildings which have so often attracted the attention of passing travellers along the High Level Bridge.

If some chares were swept away by the calamity, it must be admitted that there are still plenty left. In former days there were no less than twenty of these narrow lanes leading from the Quayside to the streets on its northern boundary. It was difficult, long before this great fire, to identify the situation of some of these by their names as given in old documents; and of course the task is by no means easier now. But some of them, at any rate, we may recall to mind. Starting, then, from the west, we note the first of the number the Dark Chare. It was so close that the houses in it nearly touched one another at the top. Then there was Grindon, Granden, or Grinding Chare. In this chare stood the remains of a remarkable house, traditionally called St. John’s Chapel. It had suffered from the ravages of change prior to the explosion, which only completed what had thus been already begun. Then there were the Blue Anchor, Peppercorn, Pallister’s, Colvin’s, and Hornsby’s Chares all forgotten now. Plummer, or Plumber, Chare is still in existence, and is supposed to have been named after a Robert Plumber who in 1378 was one of the bailiffs of the town.

If some chares were swept away by the calamity, it must be admitted that there are still plenty left. In former days there were no less than twenty of these narrow lanes leading from the Quayside to the streets on its northern boundary. It was difficult, long before this great fire, to identify the situation of some of these by their names as given in old documents; and of course the task is by no means easier now. But some of them, at any rate, we may recall to mind. Starting, then, from the west, we note the first of the number the Dark Chare. It was so close that the houses in it nearly touched one another at the top. Then there was Grindon, Granden, or Grinding Chare. In this chare stood the remains of a remarkable house, traditionally called St. John’s Chapel. It had suffered from the ravages of change prior to the explosion, which only completed what had thus been already begun. Then there were the Blue Anchor, Peppercorn, Pallister’s, Colvin’s, and Hornsby’s Chares all forgotten now. Plummer, or Plumber, Chare is still in existence, and is supposed to have been named after a Robert Plumber who in 1378 was one of the bailiffs of the town.

Fenwick’s Chare, next in order, was so named after its owner, Alderman Cuthbert Fenwick, who had his residence in it; for it must be remembered that these chares had some of the best houses of Newcastle at one time, though warehouses of various kinds now are formed in their place. The Park, or Back Lane, occurred next. Bourne in his plan of the town calls this the true Dark Chare, and so illustrates the difficulty that the inquirer has at getting to the exact truth in regard to these obscure places. Broad Garth, which came next, is not to be confounded with the much better known Broad Chare, still to come to. And then there came Peacock’s Chare, or Entry, where that remarkable man, Thomas Spence, kept his school.

Fenwick’s Chare, next in order, was so named after its owner, Alderman Cuthbert Fenwick, who had his residence in it; for it must be remembered that these chares had some of the best houses of Newcastle at one time, though warehouses of various kinds now are formed in their place. The Park, or Back Lane, occurred next. Bourne in his plan of the town calls this the true Dark Chare, and so illustrates the difficulty that the inquirer has at getting to the exact truth in regard to these obscure places. Broad Garth, which came next, is not to be confounded with the much better known Broad Chare, still to come to. And then there came Peacock’s Chare, or Entry, where that remarkable man, Thomas Spence, kept his school.

And now we have reached the Custom House, built in 1765, passing which we come to Trinity Chare, so-called because it is the back entrance to the Trinity House, which also has already been described (See vol. iii., p. 176. ). The window of the dining-room of the Three Indian Kings (a well-known Quayside hostelry) looks into Trinity Chare. The three kings are usually understood to be the three wise men from the East who brought gold, frankincense, and myrrh, in tribute to the infant Christ and his virgin mother. The sign is not an uncommon one with ancient inns.

Next to Trinity Chare is the Broad Chare. Though narrow enough to our modern notions, it is certainly the broadest chare in this locality, and almost the only one that will admit a cart. It was the common thoroughfare of the town in the olden days; now it is given up to huge warehouses and to establishments devoted to the refreshment of the inner man. Two houses figured in our illustrations were interesting specimens of the old architecture of the locality. Both pictures are copied from sketches in the late Mr. John Waller’s copy of Mackenzie’s “History of Newcastle,” now the property of Mr. J. W. Pease. The High Dykes Tavern is supposed to have somehow got its name from the fosse or ditch which surrounded the town walls, and which was called the King’s Dykes. The house shown in our other picture is alleged to have been the mansion of the Liddells of Ravensworth.

Beyond Spioer Lane, the next opening from the Quayside la the Burn Bank, where Fandon Burn used to run down into the Tyne. It was a dangerous place enough at one time. “It lies,” wrote Bourne in his day, “very low, and before the heightening of the ground with ballast, and the building of the wall and key, was often of great hazard to the inhabitants. Once, in particular.; a most melancholy accident occurred in this place. In the year 1320, the 13th of King Edward III., the river Tyne overflowed so much that one hundred and twenty laymen and several priests, besides women, were drowned, and, as Gray says, one hundred and forty houses were destroyed.’

Byker Chare, which comes next, is by Brand styled Baker Chare. The name is accounted for easily enough on the theory that it was obtained from Robert de Byker and Laderine his wife, who had lands in Pandon. On the Quay here is the chemist’s shop long associated with the name of Anthony Nichol, alderman and mayor of the town in his day, and known on the turf as the owner of the celebrated race-horse, The Wizard. Cock’s Chare comes next: so named from Alderman Cock, who lived in it. Then comes Love Lane. In the seventeenth century it was Gowerley’s Rawe. Here was born John Scott, afterwards Earl of Eldon. But it is a mistake to say, even with Mackenzie, that his brother William, afterwards Lord Stowell, and one of our foremost authorities in maritime law, was born here also. That is not so. He was born at Heworth, whither his mother had been wisely removed for greater safety, as all Newcastle at the time was in a state of alarm at the rising of the young Pretender. It is also a common mistake to suppose that the large old-fashioned house on the west side of the lane was John Scott’s birthplace. It was on the east side (faithfully depicted in our illustration), and was long ago converted into a granary.

Byker Chare, which comes next, is by Brand styled Baker Chare. The name is accounted for easily enough on the theory that it was obtained from Robert de Byker and Laderine his wife, who had lands in Pandon. On the Quay here is the chemist’s shop long associated with the name of Anthony Nichol, alderman and mayor of the town in his day, and known on the turf as the owner of the celebrated race-horse, The Wizard. Cock’s Chare comes next: so named from Alderman Cock, who lived in it. Then comes Love Lane. In the seventeenth century it was Gowerley’s Rawe. Here was born John Scott, afterwards Earl of Eldon. But it is a mistake to say, even with Mackenzie, that his brother William, afterwards Lord Stowell, and one of our foremost authorities in maritime law, was born here also. That is not so. He was born at Heworth, whither his mother had been wisely removed for greater safety, as all Newcastle at the time was in a state of alarm at the rising of the young Pretender. It is also a common mistake to suppose that the large old-fashioned house on the west side of the lane was John Scott’s birthplace. It was on the east side (faithfully depicted in our illustration), and was long ago converted into a granary.

Before we leave this part of the Quay, we ought to make mention of that remarkable candle which illuminated it in the year of grace 1770, by way of celebrating the release of John Wilkes from the prison to which he had been sent for the publication of the famous” No. 45″ of his North Briton. One Mr. Kelly manufactured a candle, which consisted of forty-five branches, cast forty-five lights, and weighed just forty-five half pounds. “The magistrates,” we are told, “adopted cautions for the preservation of the peace; but the entertainments were conducted with the greatest order and decorum.”

Before we leave this part of the Quay, we ought to make mention of that remarkable candle which illuminated it in the year of grace 1770, by way of celebrating the release of John Wilkes from the prison to which he had been sent for the publication of the famous” No. 45″ of his North Briton. One Mr. Kelly manufactured a candle, which consisted of forty-five branches, cast forty-five lights, and weighed just forty-five half pounds. “The magistrates,” we are told, “adopted cautions for the preservation of the peace; but the entertainments were conducted with the greatest order and decorum.”

We proceed along the riverside on our way eastward, leaving behind us the old historic Quay of centuries to note the peculiarities of the new. Ancient buildings we find here and there also in this comparatively modern neighbourhood; but, speaking generally, we cannot fail to remark that we are now in a neighbourhood sacred to the trade of the Tyne.

The stores and workshops of the Tyne Steam Shipping Company now claim our attention on our left hand; and, a little further, beyond the ancient “Swirle,” we find the huge pile of brick buildings known as the Grain Warehouses, with their iron doors, their ponderous lifts, and their many storeys. Near these warehouses is the eighty-ton crane another striking example of Tyneside energy; and beside and beyond it are wharves from which steamers run to London, Hamburg, Rotterdam, Copenhagan, Malmo, and other ports. And so we come to the end of the Quay proper, for the next building to be observed is the Sailors’ Bethel, a neat and commodious chapel which stands in a continuation of the Quay called Horatio Street, and forms a lasting monument of the energy and public spirit of Mr. W. D. Stephens, J.P.

Sooth to say, this part of the town is not over inviting, though the signs of business enterprise and also of rigid economy of space are both evident enough. We continue on until we come to the little bridge across the streamlet called the Ouseburn, which gives its name to the district. The road by the river, from the end of Sandgate to this bridge, is called the North Shore, and is devoted to business purposes strictly. The roadway over the stream is usually known as the Glasshouse Bridge, and consists of one arch of stone. We gather from Bourne that it was originally a wooden structure. “But,” says he, “in the year 1669, when Ralph Jennison, Esq., was mayor, it was made of stone by Thomas Wrangham, shipwright, on account of lands which the town let him. The passage, however, over it was very difficult and uneven until the year 1729, when Stephen Coulson, Esq., was mayor, [and] it was made commodious and level both for horse and foot.” The little bridge was so named from the circumstance that the glass trade had long been carried on in its vicinity.

We continue onwards, and find ourselves next at the River Police Station. Then we turn away at right angles to the Mushroom, and, proceeding northwards, speedily find ourselves in St. Lawrence Street, the end of our journey, where there is nothing to detain us. For only a very small portion of the ancient “fre chappell of Saynt Laurence in the Lordshippe of Byker” remains to give us pause. This chapel was founded, according to a document issued when the monasteries were suppressed, “by the auncesters of the late erle of Northumberland toward the fyndinge of a prieste to pray for their sowles and all christen sowls and also to herbour such (sick) persons and wayfaring men in time of nede.” Edward VI. granted this chapel to the Corporation in 1549; in 1782 Brand found its remains converted into a lumber-room for an adjoining glasshouse.

Our engravings of the High Crane, Grinding Chare, Homsby’s Chare, and the Glasshouse Bridge are reproduced from Richardson’s “Table Book.” The High Crane was situated near the Guildhall at the west end of the Quay.

Our engravings of the High Crane, Grinding Chare, Homsby’s Chare, and the Glasshouse Bridge are reproduced from Richardson’s “Table Book.” The High Crane was situated near the Guildhall at the west end of the Quay.