Following his release from captivity, William the Lion returned to Scotland with his kingdom heavily burdened by the cost of his freedom. The humiliation of the Treaty of Falaise (see my last blog – https://northeastlore.com/2021/01/30/the-second-battle-of-alnwick-1174/) triggered a number of revolts against his rule and he would spend much of his reign concentrating on bringing his own kingdom to heel. The terms of the Treaty were ended after fifteen years, when the next English king, Richard the Lionheart, agreed to relinquish the Scottish castles taken and end the taxation which he enforced that paid for the soldiers to garrison them. In return Richard sought a one off payment of 10,000 silver marks, to support his involvement in the Third Crusade.

Scotland’s independence was restored. In 1194, William made an offer to purchase Northumbria from Richard, but this was rejected. Following Richard’s death in 1199, William paid homage to his successor, King John, in 1200. The English continued to exert their dominance over Scotland however and John marched a large army to Norham on the Scottish border in 1209. This was purely a show of force with the intention of exacting money from the now aging William and also strongly proposing a marriage agreement between John’s daughter Joan and William’s only son and heir, Alexander.

William the Lion died in 1214 after reigning for 49 years (the second longest reign in Scotland before the Act of Union in 1707). His son Alexander (II) succeeded him. In 1215, Alexander joined the cause of the English baron’s rebellion against King John, leading an army south. After sacking Berwick upon Tweed his army ravaged the north, ultimately reaching the south coast of England. He even went so far as to pay homage to King Louis VIII of France who had been chosen by the Barons to replace John. However, John died in 1216, and his son Henry III was proclaimed King before the French could take the throne. Peace between the three kingdoms was secured in 1217 with the Treaty of Kingston and Alexander returned to Scotland beginning a period of relative peace on the border. Tensions rose in 1237 when Alexander once more raised the spectre of his hereditary claims to lands in northern England. The dispute was settled peacefully by the Treaty of York, which defined the border between England and Scotland once and for all. Other than a brief threat of English invasion in 1243, peace between England and Scotland remained in place for the time being.

Alexander II died in 1249 and was succeeded by his seven year old son, Alexander III. Two years later, Alexander married Margaret, daughter of Henry III of England (he was ten and Margaret was nine!). Henry used the marriage as an opportunity to demand that his new son-in-law pay homage for Scotland. The young Scottish king refused. His reign marked a time of relative peace and prosperity for Scotland. He and Margaret had three children. Their eldest child, a daughter called Margaret after her mother, married King Eric II of Norway. Their eldest son, Alexander, was raised as heir to the throne and a second son David (the spare) seemed to secure the Royal line. All seemed set for a smooth succession and a continuation of the stable government which had been enjoyed for some years. As often happened, however, disaster struck. Between 1275 and 1284 Alexander III’s wife and all three of their children died.

Alexander had not re-married following his wife’s death and the next in line to the throne was his young granddaughter, Margaret, the Maid of Norway. He hastily arranged a marriage for himself to Yolande de Dreux of France, with the express aim of getting a new male heir to succeed him and she indeed duly became pregnant. Misfortune occurred in March 1286 when, despite being urged not to, he rode through the night, in a storm, to meet his new wife for her birthday. In the atrocious weather, over treacherous terrain, his horse lost its footing, and the King was killed after being thrown from the saddle. He died the day before his wife’s birthday. Possibly in her grief Yolande lost her baby, the unborn heir or heiress, and the succession passed to the seven year old Maid of Norway. Margaret was never crowned, however. In 1290, while she was on her way to her new kingdom, her ship sank in a storm.

At this time, England was ruled by the warrior king, Edward I. Going by the moniker “Longshanks” on account of his height (6’2”), he was ruthless and a master tactician. Fresh from his success in subduing the Welsh, Edward’s ambitions in Scotland were, to begin with, restricted only to diplomacy. Following the death of Alexander III, Edward proposed that the new queen, Margaret, should marry his son (the future Edward II). His long term goal was that this union would eventually bring Scotland under English rule. Following Margaret’s death, however, Scotland was yet again plunged into a succession crisis. In the power vacuum, Edward I was asked to arbitrate on the claims of those who thought that they should be the next king of Scotland. In an unsubtle move to exert his dominance, Edward chose the weak and vacillating John Balliol as the next king. By 1295 John’s rule was that of a puppet to Edward and it was clear that the English King had designs on conquest.

The Scottish response was to seek a lasting and historically important alliance with England’s enemy, France, the “Auld Alliance”. In March 1296 Edward I mustered an army of some 25,000 and reaching Berwick upon Tweed he slaughtered almost the entire population of 11,000. By July, the campaign was over, and Edward declared himself King of Scotland. He returned to England with the “Stone of Destiny”, the single most potent symbol of Scottish independence. He also bought with him the dethroned John Balliol to be locked in the Tower of London. John would be known to history as “Toom Tabard” (meaning empty coat) in reference to him being stripped of his royal vestments. He was released in 1299 and died in France fourteen years later. We’ll follow the story of his son, Edward Balliol, in a subsequent blog.

Edward’s invasion of Scotland in 1296 was the start of what is referred to as the First War of Scottish Independence. English subjugation of Scotland did not go unchallenged for long and in 1297 the country erupted into open revolt. Andrew de Moray and William Wallace emerged as the principal leaders. If you have seen the 1995 film Braveheart, you will have been presented with a romanticised semi-historically accurate version of these events. Multiple insurrections boiled away and when the English raised an army to confront the rebellious Scots it ended at the Battle of Sterling Bridge (the absence of a bridge in the Braveheart depiction of the battle is a constant annoyance whenever I watch that film!). The Scots were clever, using the terrain and English tactics against their enemy. It resulted in a resounding Scottish victory which would drive the English out of Scotland. Damagingly for the Scots, Moray was killed in the battle, but Wallace kept up the momentum and launched an invasion of northern England. He laid waste to Northumberland and Cumberland with hundreds of refugees seeking shelter behind the walls of Newcastle. In March 1298, Wallace was knighted and made Guardian of Scotland in the name of the exiled John Balliol.

Enraged by this ignoble rabble rouser, Edward I made preparations to invade Scotland once more to crush the rebellion. In July 1298 his army found Wallace near Falkirk. Although he was a magnetic leader and superb guerrilla fighter, Wallace perhaps lacked the military experience to face the English in the field on his own. Many sources reckoned on the late Moray having been the master tactician best able to lead to victory the Scots on the battlefield and that Wallace was the popular guerrilla leader. The subsequent battle ended in defeat for Wallace who was outnumbered (probably two to one) and ‘out-gunned’ by the English longbowmen who decimated his static schiltron formations (a tactic that the Scots would come to fear). His reputation in tatters, Wallace never recovered. Wanting to make a particular example of him, Edward I put a lot of energy into hunting him down. Wallace was finally captured in 1305 and taken to London where he was hung, drawn and quartered as a traitor.

As descendants of David I, the Bruce family had some claim to the throne of Scotland after the disaster following the death of Alexander III. The youngest scion of that house was Robert the Bruce. He joined the rebellion against Edward I to back up the claim of his father (also Robert) who was Lord of Annandale. Others noble houses also sought to advance their own claims to kingship. Following the defeat of Wallace at Falkirk, Robert (known as “the Bruce”) was made Guardian of Scotland in 1298 alongside a rival claimant for the throne, John Comyn and the Bishop of St. Andrews, William Lamberton. Bruce resigned this post in 1300 due to escalating tension with Comyn and the rumour that John Balliol would soon be restored to the throne. After a further punitive military expedition in 1303, all the Scottish nobles bent the knee to Edward I. It seemed as though Edward had succeeded in subjugating his northern neighbour. One of his well earned soubriquets was Malleus Scotorum or “Hammer of the Scots”.

In 1305, Comyn made a secret agreement with Bruce to forfeit his claim for the throne in return for Bruce’s lands in Scotland, should Robert start a fresh uprising. In a sly and calculating move, it seems Comyn told Edward I of this meeting – which made Bruce a wanted man. Bruce arranged to meet with Comyn at the Grayfriars Monastery, Dumfries, in February 1306. Bruce accused Comyn of treachery and a fight broke out. Bruce stabbed Comyn before the high alter, and his men finished him off. Bruce immediately went to Glasgow, where his friend and supporter Bishop Robert Wishart granted him absolution. Nonetheless, Bruce was excommunicated by the Pope for the heinous crime of killing on consecrated ground (no small matter in the Medieval world).

Bruce then decided to act on his claim to the Scottish throne. Six weeks after Comyn was killed, Robert the Bruce was crowned King of Scotland at Scone on Palm Sunday 1306. Bruce rallied Scottish support and spent the next eights years leading a successful guerrilla campaign against the English. Scottish fortunes improved when, in July 1307 the aging, yet still fearsome “Hammer of the Scots”, Edward I, died at Burgh by Sands near the Solway Firth. He was on his way with another army following the English Defeat at Loudoun Hill. He was succeeded by his son Edward II. Viewed as a weak shadow of his warrior father, Edward II was not up to the job of quelling the uprising against English rule. Matters came to a head in 1314 with the crushing defeat of the English at the famous Battle of Bannockburn, fought just south of Sterling. English losses were huge, with perhaps as many as 700 knights and men-at-arms and 11,000 infantry being killed and with 500 knights and men-at-arms captured. Scottish losses in comparison were relatively light. A number of English nobles who were captured were exchanged for Robert’s wife and children as well as the stalwart Bishop Wishart, all of whom had been imprisoned in England. The defeat of the English left the border undefended and the Scots were able to raid Northumberland and Cumberland unopposed.

In 1320, in response to Bruce’s excommunication, a letter called the Declaration of Arbroath, was sent to the Pope demanding the recognition of a fully independent Scotland. It also denounced English attempts to subjugate it and sought justification for the right for Scotland to defend itself militarily when unjustly attacked. The Pope did eventually lift the excommunication placed on Robert and peace talks were held between the warring kingdoms in the early 1320’s. However, the English still refused to recognise Robert the Bruce as King of Scotland and maintained their claim to the throne of Scotland. A truce was agreed in 1323 although sporadic clashes would occur.

The remainder of Edward II’s rule was spent dealing with rebellion in England following the elevation of the sycophantic Despenser family and war with France. In the end, he was deposed and forced to abdicate by his wife Isabella (known to history as the She-Wolf of France) and her lover Roger Mortimer. His young son Edward was crowned on 2nd February 1327 in his place. It is interesting and somewhat grizzly to read about what may or may not have happened to Edward II. Some thought he was unfairly treated, and a cult grew up around his legacy with many thinking he should be made a saint. Edward III was only 14 when he was crowned, and it was clear that Isabella and Mortimer intended to control the young man. From these difficult beginnings he would grow into one of the most successful medieval kings of England, but that is another story. The subject of this blog occurred in the very first year of Edward III’s reign and the experience would stay with him for the rest of his life. What he learned during the 1327 Weardale Campaign likely influenced the military tactics he would employ to such devastating effect against the French and Scottish later in his reign.

Due to the perceived weakness of the new boy king on the throne in England and backed up by a renewal of the Auld Alliance with France, Robert the Bruce felt the time was right to resume hostilities and force the recognition of the independence of his kingdom. In June 1327 a large Scottish army, under the command of James Douglas and the Earls of Mar and Moray crossed the border into Northumberland. By this time Robert’s health was failing and he did not join his men.

Isabella and Mortimer had been expecting an attack and had already mustered an army at York to counter the threat. Edward III was in a precarious position and desperately need to prove himself. A medieval king held absolute power, but he did so on the proviso that he would be able to defend his people. Failure to act would give the impression that he was no different from his father, the king who “lost Scotland”. Accordingly, despite his young age, he led the English army north to meet the Scottish threat head on.

Scottish raiding tactics of the time involved spreading out over a wide area to loot, burn, murder, and steal cattle (the principal livelihood in the north). The idea was to cause maximum destruction and maximum terror over huge swathes of land before marching back over the border to count their loot. The Scots were hardy men and masters of manoeuvrability. They travelled very light, carrying only their weapons, and living off the land, constantly on the move.

Froissart, in his Chronicles, tells us: Since they are sure to find plenty of cattle in the country they pass through, the only things they take with them are a large flat stone places between the saddle and the saddle cloth and a bag of oatmeal strapped behind. When they have lived so long on half-cooked meat that their stomachs feel weak and hollow, they lay these stones on a fire and, mixing a little of their oatmeal with water, they sprinkle the thin past on the hot stone and make a small cake, rather like a wafer, which they eat to help their digestion.

When an army was sent to stop them, they were able to disperse and melt away, rarely getting drawn into a pitched battle.

Disparate reports of the Scottish host came in from English scouts but try as they might the English army could not track them down. The army could see the plumes of smoke taunting them: evidence of the elusive raiders. As time went by and tensions frayed in the disheartened ranks, it was decided that instead of hunting the Scots down, they would march north to block the Scottish route back north. The English army camped first at Haydon Bridge and then at Haltwhistle to await the enemy. More time elapsed with no sign of the Scottish army and the hardship of keeping so many men in the field began to take its toll on the dispirited English army.

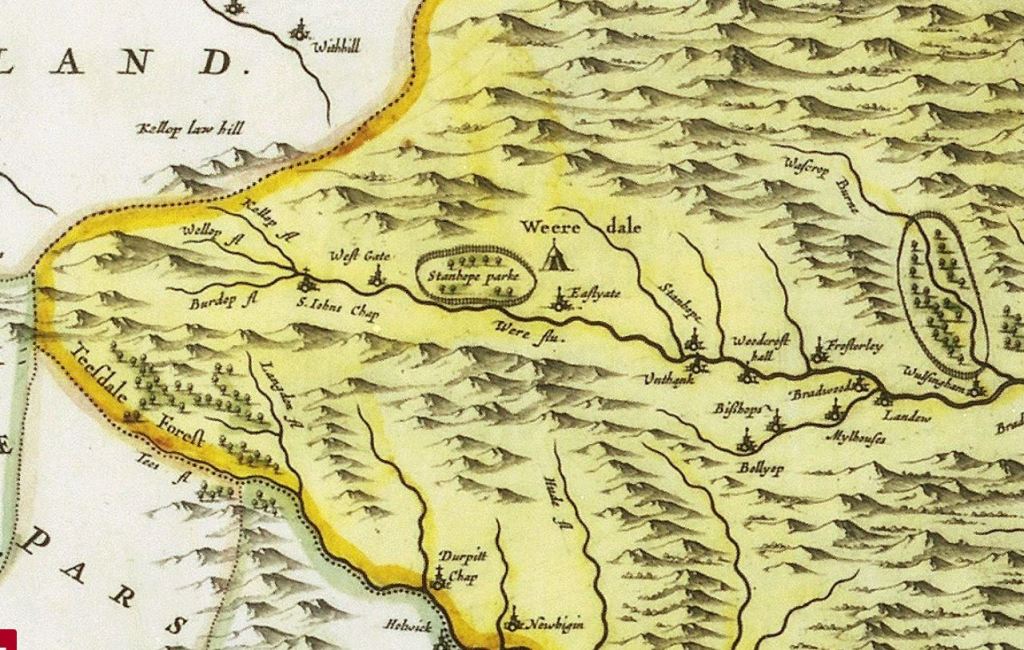

Towards the end of July, an English esquire named Thomas Rokesby, who had been scouting, came upon the Scottish host in Weardale near Stanhope Park (at the time Stanhope Park was a hunting reserve of the Bishops of Durham). It was located just to the west of the modern market town of Stanhope, along the A689 between the villages of East Gate and West Gate – named literally after the gates to the park. Thomas was captured but allowed to leave with his life on the proviso that he deliver a message to the English king – that the Scots had as much desire to fight and would wait for Edward III to arrive. The English army marched south. On their arrival they were horrified to see that the Scots had arrayed themselves in a strong defensive position. They had formed up into three large schiltron formations on the slope of a hill close to the River Wear. The English, on the other side of the river, made camp and pondered how they could cross the river and attack without being decimated in the process. The English knew that swampy ground lay to the north of the Scottish position and reasoned that they were trapped. With the English blocking their path to the south it effectively would turn into a siege with the English waiting for the Scots to run out of what little supplies they had. Despite the Scots challenge, they would not give up their formidable position by attacking and a stalemate ensued.

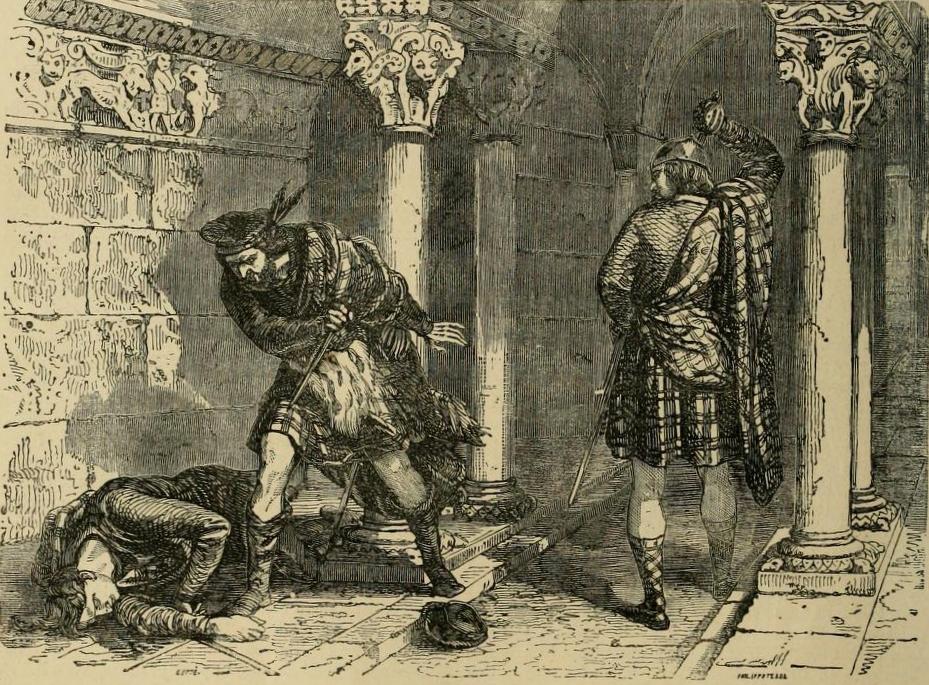

The Battle of Stanhope Park refers to an action on the first night that the English made camp. Sir James Douglas, known as “Black Douglas” was a Scottish knight and lord. Born in 1286, he had been one of the prominent commanders in the war with England to date and fought with ferocity at Bannockburn. In 1318 he was instrumental in capturing Berwick back from the English. On the night of 4th August 1327 Douglas led a group of Scottish men-at-arms in a surprise attack on the sleeping English. Not expecting such a bold move, panic and confusion ensued and Douglas’s men managed to reach the tent of the 14 year old Edward III himself. Froissart describes it as follows: The Lord James Douglas took with him about two hundred men-at-arms, and passed the river far off from the host so that he was not perceived: and suddenly he broke into the English host about midnight crying ‘Douglas!’ ‘Douglas!’ ‘Ye shall all die, thieves of England’; and he slew three hundred men, some in their beds and some scarcely ready; and he stroke his hose with spurs, and came to the King’s tent, always crying ‘Douglas!’, and stroke asunder two or three cords of the King’s tent.

Thinking that this attack heralded a full scale assault, the English camp made ready, lighting huge bonfires and fortified their position. The attack never came and after three days the English found that the Scots, under cover of darkness, had managed to pick their way through the swamp to march back home. Realising they had failed in bringing the Scots to heel, the English army marched back to York. Sir Thomas Grey in his Scalacronica, states simply the “The King, an innocent, wept”.

The inconclusive campaign was a great setback for the English and the new king. The Treaty of Northampton, signed in the following year, conceded all the Scottish demands, including the recognition of Robert the Bruce as King of an independent Scotland. At this price, peace was secured for a few years.

Edward III’s experiences during this campaign must have affected him deeply. He resolved never to be the victim of circumstance again. By 1330 he had executed his mother’s lover Roger Mortimer and sent his mother into “retirement” and his personal reign began.

Edward III would go on to have one of the longest and most successful reigns of any medieval English monarch. Some of the military tactics which he and his son The Black Prince would deploy in the 100 Years War against France (massed archery, fighting on foot and the highlight mobile chevauchee) were developed from his experiences fighting the Scots. Not content with the peace agreements which had been made in his name (the Treaty of Northampton) Scotland would not know peace for long (of which we will discuss more in the next blog).

Robert the Bruce died in 1329. He is, rightly, remembered and revered as one of Scotland’s national heroes. Despite his victories and the recognition of his Kingdom’s independence, the war with England was not won and his descendants and successors would fight against the English for years to come. What Robert’s legacy provided more than anything else though, was hope and the pride that victories like Bannockburn instilled into the national conscience. It reminded the Scots that, whatever the odds, the English could be beaten.

If you are interested in reading more about this subject, then I would very much recommend the following books:

- Scalacronica, Sir Thomas Grey (edited and translated by Andy King).

- Chronicles Froissart, (Penguin Classics).

- War Cruel and Sharp – English Strategy under Edward III 1327 – 1360, Clifford Rogers.

- Border Fury: England and Scotland at War 1296-1568, John Sadler.

I liked the bit about Douglas cutting the stays of the King’s tent then disappearing and never coming back.

LikeLike

I did too. A bit of a middle finger to the English 🤣

LikeLike

Hi. My name is John Bailey of the Battlefields Trust, researcher of The Weardale Campaign and The Battle of Stanhope Park, and I have a family connection to Stanhope village. The Battlefields Trust has posted my findings on its Battlefield’s hub.https://www.battlefieldstrust.com/resource-centre/medieval/battleview.asp?BattleFieldId=97

I have also produced a Youtube film of the battle, courtesy of Tony Fox. https://youtu.be/RGgNhM9KcLU

Thank you.

Regards John

LikeLike

Thanks for your comment John…hope I got the content about right. Would really appreciate any comments / amends if you noticed any. I’ll check out your video too.

LikeLike

Hi,very interesting read.

We do as volunteer research on hylton castle,Sunderland and we are trying to find out which knights from the castle were involved.

Do you have anything on this.

Or can you direct us to the best area.

Thanks

Alf Scott

LikeLike

Hi Alf…do you mean did Alexander de Hylton (2nd Baron) fight at the Battle of Stanhope?

LikeLike