The lighting of towns in our island, by combined effort, is of modern date. Even in the metropolis it had no existence prior to the last century. So far back as the reign of the hero of Agincourt, there was, indeed, street-lighting; but in a sorry, makeshift sort of way. When Christmas was at hand, in the year 1418, as festivities would then be on foot, and wine would be in and wisdom out, an order was made that each honest person dwelling in the City should set “a lantern, with a candill therein,” before his house, in promotion of the public peace. An expedient of the like homely kind was also resorted to at Newcastle in the seventeenth century, more especially in seasons of civil commotion.

Whether systematic street-lighting was first adopted in England or on the Continent is an open question. “Of modern cities,” says Beckmann, “Paris, as far as I have been able to learn, was the first that followed the example of the ancients by lighting its streets.” Yet in 1524 it was still content with lights exhibited before the door by the citizens; but about the middle of the century there were brasiers in the thoroughfares, with blazing pitch, rosin, &c., dispelling (or at least mitigating) the murkiness of the atmosphere by night. Almost immediately afterwards, in 1558, came street lanterns; and in little more than a hundred years, an enterprising Italian abbe was in Paris, letting out lamps and torches for hire, and providing attendants. His operations were extended also to other cities; while not only was all Paris now lighted by its rulers, but even the outskirts: for nine miles of lamps extended as far as Versailles. In London, meanwhile, in the latter years of the seventeenth century, householders were admonished as of yore to hang out a light every night from Michaelmas to Lady Day. It was a device by which the gloom of the metropolis after nightfall was but imperfectly relieved. How it fared with the citizens in their benighted paths may be conceived from the pages of the poet Gay, who published his “Trivia, or the Art of Walking the Streets,” in the reign of Queen Anne. To all who might stumble into danger unwarily, he gave this word of caution:

Though thou art tempted by the linkmairs call,

Yet trust him not along the lonely wall;

In the mid-way he’ll quench the flaming brand,

And share the booty with the pilfering band;

Still keep the public streets, where oily rays,

Shot from the crystal lamp, o’erspread the ways.

The ineffectual fires of these crystal flickerers hardly served to make visible the increasing accumulations that addressed themselves, in almost every town of the time, to the more prominent feature of the face. “I smell you in the dark,” muttered Johnson to Boswell, passing along the High Street of Edinburgh on an autumn night of 1773; and Gay sounded his warning note in London:

Where the dim gleam the paly lantern throws

O’er the mid-pavement, heapy rubbish grows.

There were also roysterers of the night, ready for a brawl, yet respecters of persons; topers who, observant of the better part of valour,

Flushed as they are with folly, youth, and wine,

Their prudent insults to the poor confine;

Afar they mark the flambeau’s light approach,

And shun the shining train and golden coach.

So sung Johnson in his “London” in the year 1738, when Parliamentary powers had recently been obtained for the establishment of corporate lighting by night. A Bill was introduced for street-lighting in 1736; and in the ninth year of the reign of George II. the Royal Assent was given to “An Act for the Better Enlightening the Streets of the City of London.”

When the eighteenth century, whose midnights had been visited by the glare of flambeaux and the glimmer of oil-lamps, closed its course, it was casting before it the splendour of gas. A hundred years earlier, indeed, the Dean of Kildare, Dr. Clayton, had liberated ” the spirit of coal.” “Distilling coal in a retort, and confining the gas produced thereby in a bladder, he amused his friends by burning it as it issued from a pin-hole.” It afterwards became a common amusement to fill a tobacco pipe with crushed coal; thrust the bowl into the fire; and light the gas jet as it flowed from the stem. This was a toy. But William Murdock, a native of Ayrshire, put gas to work in earnest. In 1792, residing at Redruth, in Cornwall, as the representative there of Boulton and Watt, he lighted up his house and offices with “the spirit of coal,” and in the general illumination of 1802, in celebration of the Peace of Amiens, he wrapped the whole front of the famous Soho Works in a flaming flood of gas, dazzling and delighting the population of Birmingham, and publishing the new light to the world! Its success was so decided that the proprietors had their entire manufactory lighted with gas; and several other firms, in various parts of the country, followed their example.

“New lights” have ever to contend with old. However brilliant their promise, there is the shadow of incredulity, the gauntlet of ridicule. Oracular heads were shaken at gas. As well think of lighting a town with “clipped moonshine,” was their contemptuous conclusion; while the alarmists anxiously inquired, “if gas were adopted, what would become of the whale fishery?” The world, careless whether the whale should survive the change, listened to Murdock.

One of Murdock’s most enthusiastic disciples Winsor, a German introduced the light into London in 1807. Winsor applied to Parliament for a Bill, and Murdock was examined before the committee. “Do you mean to tell us,” asked one member, “that it will be possible to have a light without a wick?” “Yes, I do, indeed,” answered Murdock. “Ah, my friend,” said the legislator, “you are trying to prove too much.” It was as surprising and inconceivable to the honourable member as George Stephenson’s subsequent evidence before a Parliamentary Committee to the effect that a carriage might be drawn upon a railway at the rate of twelve miles an hour without a horse. Even Sir Humphry Davy ridiculed the idea of lighting towns with gas, and asked one of the projectors if it were intended to take the dome of St. Paul for a gasometer! The first application of the “Gas Light and Coke Company” to Parliament in 1809 for an Act proved unsuccessful; but the “London and Westminster Chartered Gas Light and Coke Company” succeeded in the following year. The company, however, did not prosper commercially, and was on the point of dissolution, when Mr. Clegg, a pupil of Murdock, bred at Soho, undertook the management, and introduced a new and improved apparatus. Mr. Clegg first lighted with gas Mr. Akerman’s shop in the Strand in 1810, and it was regarded as a great novelty. One lady of rank was so much delighted with the brilliancy of the gas-lamp fixed on the shop-counter, that she asked to be allowed to carry it home in her carriage, and offered any sum for a similar one. Mr. Winsor, by his persistent advocacy of gas-lighting, did much to bring it into further notice; but it was Mr. Clegg’s practical ability that mainly led to its general adoption. When Westminster Bridge was first lit up with gas in 1812, the lamplighters were so disgusted with it that they struck work, and Mr. Clegg had himself to act as lamplighter. (Smiles’s “Lives of Boulton and Watt.”)

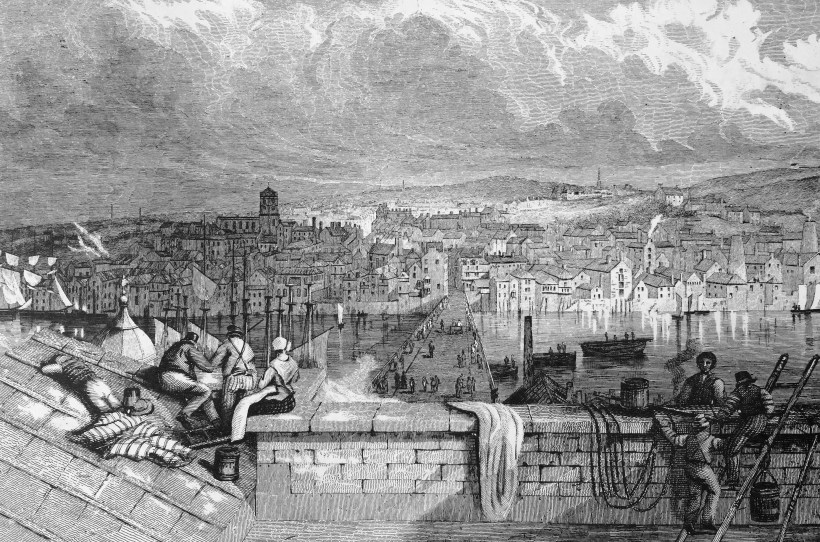

One of the earliest provincial towns to adopt the new light was Newcastle-upon-Tyne. This was in 1818; of which year Smiles has a characteristic anecdote relating to Murdock. He had come to Manchester to start one of Boulton and Watt’s engines, and, with Mr. William Fairbairn (from whom the biographer had the story), was invited to dine at Medlock Bank, then at some distance from the lighted part of the city. “It was a dark winter’s night, and how to reach the house, over such bad roads, was a question not easily solved. Mr. Murdock, however, fertile in resources, went to the gas-works, where he filled a bladder which he had with him, and, placing it under his arm like a bagpipe, he discharged through the stem of an old tobacco-pipe a stream of gas, which enabled us to walk in safety to Medlock Bank.”

Before going any further, let us observe that public lighting is of considerable antiquity on the Tyne. In the month of November, 1567, a dozen years before Parliament was considering a Bill for maintaining a light on Winterton steeple, “for the more safety of such ships as pass by the coast,” the Corporation of Newcastle was paying 3s. “for 4lb. of waxe maid in candell for the lanterne of Sancte Nyciolas Churche, and for the workynge.” Such items were not uncommon. Here is another, of the month of December ensuing: “For 2lb. of waxe, wrought in candell for the lanterne in Sancte Nycholas Churche, 1s. 6d.” There were lights aloft on the church tower for the comfort and guidance of wanderers over the open country, whose feet were in anxious search of the Metropolis of the North.

In town and country men had then to grope their way by night. At a much later date than the reign of Elizabeth, how darksome were the streets of Newcastle!

There is an instructive anecdote of Lord Eldon, reviving the days when the future Lord Chancellor was on the threshold of his teens, and lighting by Act of Parliament was unknown on the Tyne. He and his schoolfellows would forgather on a winter’s night at the Head of the Side, on boyish freaks intent. It was a time when shops were unglazed, the windows open to the outer air, and the interior feebly lighted by a lamp or a “dip.” Down the Side the youngsters would start for the Sandhill; and first one, then another, would drop on his knees at a tradesman’s door, creep across the floor, lift up his lips, and blow out the flame! Hasty then was the retreat; and the merry band were off in pursuit of another victim, till all the shopkeepers in the row were reduced to dipless darkness.

The reign of George II. had to pass away before the aid of Parliament was successfully invoked for lighting the streets of Newcastle. The Common Council, which in 1717 had applied for an Act, again took up the matter; and soon after the accession of George III. powers were obtained. In the spring of 1763, Newcastle obtained an Act for lighting and watching the town, and regulating the hackney-coachmen and chairmen, the cartmen, porters, and watermen; and on Michaelmas Day the oil lamps were a glow to the best of their ability.

Whether the Act of 1763 spoiled the fun of Young Newcastle, and threw oil on the troubled waters of the tradesmen, our annalists do not say. But doubtless the schoolboys of the good old days “when George the Third was King” found abundant channels in which to gratify their love of mirth and mischief. For half a century and more the ladder of the lamplighter was in alliance with the harpoon of the whaler. But when the age of gas had arrived, the metropolis of the coalfield could not hold back, whatever came of the whale-fishery. In the dawn of the long reign of George III., Newcastle had received powers for lighting by oil; and near its close it was applying for an Act for lighting by gas. The requisite powers were granted. On the 10th of January, 1818, on which day the Savings Bank was first opened, gas-lighting also began. “In the evening,” says Sykes, “a partial lighting of the gas-lights took place in such of the shops in Newcastle as had completed their arrangements. The lamps in Mosley Street were not lighted till the 13th (Tuesday evening), when a great crowd witnessed their first lighting up, and a loud cheer was given by the boys as the flame was applied to each burner.” Collingwood Street had its illumination on the 26th; and the Old Assembly Rooms in the Groat Market, occupied by the Literary and Philosophical Society, were lighted on the 27th. Before the end of the month gas-lighting was becoming general. “This beautiful light,” says the Newcastle Chronicle, “is now introduced into most of the shops in the streets through which the pipes have been carried, and thus the thorough-fares are rendered in the evening beautifully resplendent.” The theatre was first lighted with gas on the 3rd of March.

Newcastle having led the way, other Northern towns were not slow to follow. North Shields was lighted with gas in 1820; Berwick-upon-Tweed and Stockton-upon-Tees in 1822; Durham in 1823; Sunderland in 1824; South Shields in 1826; and Darlington in 1830. Gas had passed into general favour. Instances occurred, however, in which tradesmen were admonished that if they had the “new light” in their shops they must not expect to see their old customers; and some cautious folk, providing for their safety, retired to watering-places or elsewhere ere the gas-lamps were lighted! They would have had their neighbours walk in the ancient ways, and stand by the whale.

Slowly street-lighting had moved onward in the olden time. Through long generations the householders were contributing each his candle to the public service. Twinkling stars of light strove through “the blanket of the dark,” producing an effect on which the “sickly glare” of oil was subsequently thought to be an improvement! But the rate of progress has been accelerated in modern days. Half-a-century sufficed to make an end of oil in the streets of Newcastle; and now, after less than four-score years more, gas is in controversy with the electric flame.

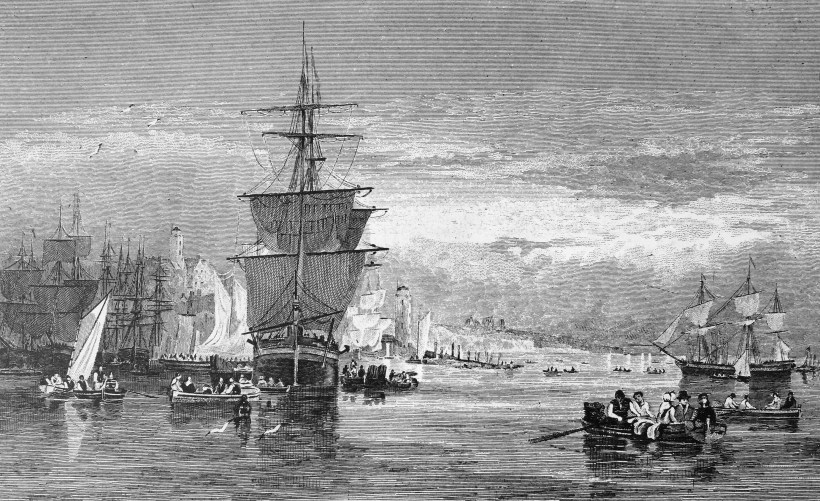

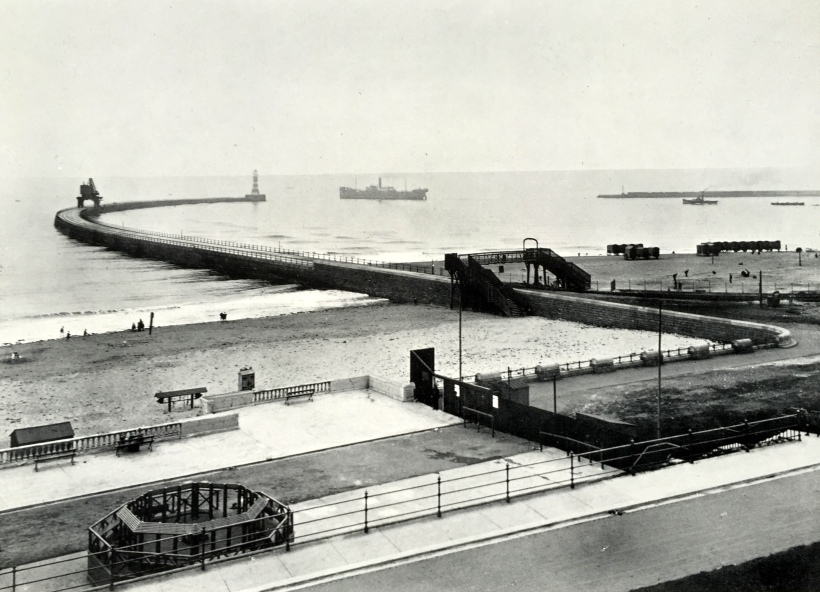

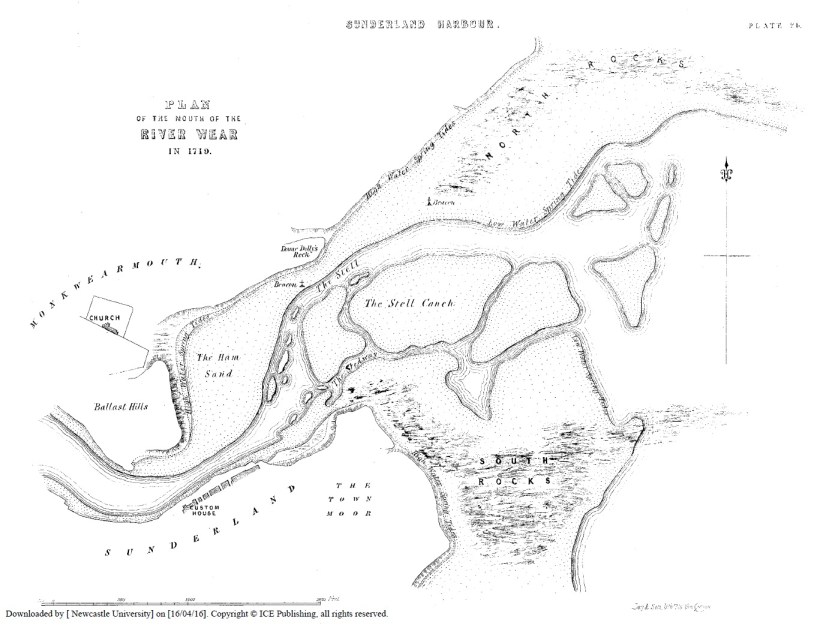

It was in June, 1850, that Mr. W. E. Staite, a pioneer and patentee of electric lighting, exhibited his light from the South Pier, Sunderland. Mr. Staite had been invited by the Commissioners of the River Wear to show his invention, in order that, if found suitable, it might be adopted as the permanent means of illuminating the New Dock. Great interest was manifested in the exhibition throughout the town; and towards evening thousands thronged the piers and quays, while many availed themselves of trips to sea so as to witness the effect of the light several miles from land. The apparatus was erected upon a temporary platform, raised a few feet above the lighthouse, the galvanic battery being placed in a shed below. At ten o’clock exactly the spectators on shore were gratified by the first glimpse of the light, which was shown with a parabolic reflector. It was directed towards Hartlepool, Seaham, and Ryhope, and then brought gradually northwards by the reflector being moved slowly round. The light was then sent successively upon the Docks, St. John’s Chapel, the quays, piers, and then towards Roker and Whitburn. A few nights later, between eleven and twelve o’clock, on the 25th of June, 1850, Mr. Staite exhibited the light at the Central Railway Station, Newcastle, to the directors of the company and a numerous party. The inventor had been asked to give a tender for lighting the station, which he did, but the directors did not see their way to adopt it.

Mr. Staite’s visits were naturally recalled to mind on the eve of the first lecture of our townsman. Mr. J. W. Swan, whose name is now everywhere familiar. This lecture was given before the Literary and Philosophical Society of Newcastle early in 1879. Not a few were then present who remembered how, on the occasion of the marriage of the Prince and Princess of Wales in 1863, Mr. Swan threw down from the Shot Tower and St. Mary’s the flooding light of

The shining sun that mocked the glare

Of envious gas, struck pale and wan.

And the whole of the brilliant audience brought together in 1879 saw the same docile flame hermetically imprisoned, like some genius of the Arabian Nights, within walls of glass, and diffusing around it the soft lustre which the drawing-room desires.

The world is ever making new conquests, while not throwing aside the old. Society is not unthrifty. It adds to its roll of handmaids. Further arrivals do not foreshadow the departure of their forerunners. There was, as we have seen, in a former generation, an alarm for the whale fishery; and yet, the cry was so groundless. that it has given place to a fear lest the whale fishery, in the persistent and growing consumption of oil, should become extinct. Oil, indeed, is in such demand that the earth itself has been harpooned. On land as on sea oil is struck; and the mineral supply sheds its serene light over a million firesides. Oil, and gas, and candle have yet a long lease of social service to run; while the electric light has before it a career but dimly seen in our brightest dreams.